Vincent van Gogh and

Lester Flatt. Vincent van Gogh and

Lester Flatt.Merle Haggard and Claude Monet. Makes sense to Marty Stuart. He puts the work of all these men under the category of “museum-quality art.” Lately, the museums are in agreement. “The Frist is part of our spring world,” says Stuart, the “Grand Ole Opry” star whose work behind camera lenses is the star of a new exhibit at The Frist Center for the Visual Arts called American Ballads: The Photographs of Marty Stuart and of a forthcoming (due for a July 4 release) Vanderbilt University Press book of the same name. “Later this year, we’re at the Smithsonian,” Stuart says. “This fall, it’s the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I’ve been working on getting our culture to be weighed in alongside jazz, ballet and theater. Now, these institutions are responding.” It’s telling that Stuart’s work as a photographer and documentarian and his subjects’ work as performers of simple songs are recognized as entities of cultural significance. It’s also telling that The Frist Center, which opened in 2001, is recognized as a place of international renown and a major museum worth mentioning in the same breath as the Smithsonian or the Met. The artist and the museum have attained such status by embarking on similar missions: They each survey their immediate surroundings and the world at large with jewelers’ eyes, seeking people and things that are special and then illuminating those people and things so that the rest of us can have a better understanding.  Inspired by his mother,

Hilda Stuart, whose photographs are published in a

Nautilus Publishing book called Choctaw Gardens,

Stuart began taking photographs when he was 11. His

first one was of the headline performer at the

Choctaw Indian Fair in Stuart’s hometown of

Philadelphia, Mississippi. That performer was Connie

Smith. Today, she’s a Country Music Hall of Famer,

and Stuart is married to her. Inspired by his mother,

Hilda Stuart, whose photographs are published in a

Nautilus Publishing book called Choctaw Gardens,

Stuart began taking photographs when he was 11. His

first one was of the headline performer at the

Choctaw Indian Fair in Stuart’s hometown of

Philadelphia, Mississippi. That performer was Connie

Smith. Today, she’s a Country Music Hall of Famer,

and Stuart is married to her.Stuart moved to Nashville when he was 13, over Labor Day weekend of 1972, to work as Flatt’s mandolin player. Soon, he found himself on tour with Flatt in New York, and he saw the striking, black-and-white photographs that Milt Hinton took of jazz greats Louis Armstrong, Billie Holliday, Miles Davis and others. Stuart soon called his mother and asked her to mail him a camera. “He knew he could do for country what Hinton had done for jazz, and the timing was perfect,” writes Frist Executive Director and CEO Susan H. Edwards in her essay at the outset of the “American Ballads” book. “The arc of Stuart’s career placed him no more than two degrees of separation from every legend of country music, living and dead. Moreover, Stuart was keenly aware of how quickly country music was changing, and he wanted to be the memory keeper.” Photos win raves Stuart’s musicality and affable personality afforded him access that a backstage pass never could. His attention and perspective allowed him to turn that access into art.  He took

photos of “Father of Bluegrass” Bill Monroe on his

Goodlettsville farm, the rare place where free-range

chickens and late-model limousines intersected. He

captured Jerry Lee Lewis, extending middle fingers

over drinks in Paris, and Johnny Cash and Ray

Charles howling with laughter at a Nashville

recording session produced by Billy Sherrill. He took

photos of “Father of Bluegrass” Bill Monroe on his

Goodlettsville farm, the rare place where free-range

chickens and late-model limousines intersected. He

captured Jerry Lee Lewis, extending middle fingers

over drinks in Paris, and Johnny Cash and Ray

Charles howling with laughter at a Nashville

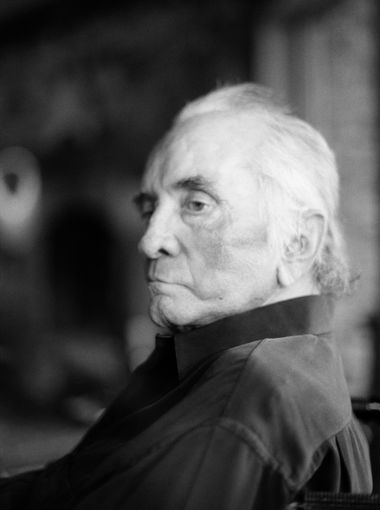

recording session produced by Billy Sherrill.He shot Hank Williams Jr. and his daughter, Katie, at the gravesite of Hank Williams, and he shot “King of Bluegrass” Jimmy Martin at Martin’s own grave. (The King took a proactive approach to perpetuity.) The most striking music portrait may be of Cash, addressing not the camera but his own mortality, on September 8, 2003, four days before his death. American Ballads is not exclusively devoted to country musicians. There’s also a section called “Badlands,” filled with portraits of the Lakota people of South Dakota, and another called “Blue Line Hotshots,” filled with characters Stuart has met on the road. “All of these are folk heroes to me,” he says. “The common denominator between them and the country music masters is the fierce sense of individualism and independence they all share.” Edwards, who worked with Frist curator Kathryn Delmez (who edited the Vanderbilt Press book) on the exhibit, is a photography historian who has come to admire the work of country music-oriented Nashville photographers including Stuart, Les Leverett and Jim McGuire. Stuart’s status as a master musician didn’t sway her opinion of his photographs: She was appropriately swayed as soon as Delmez showed her samples of Stuart’s work. “His work holds up, or it wouldn’t be in a museum,” she says. “Marty Stuart is a serious photographer, and his photographs transcend his renown. He would be considered an outstanding documentarian in any genre. That he happens to live in Middle Tennessee is our good fortune.” If You Go What: “American Ballads: The Photographs of Marty Stuart” exhibit Where: The Frist Center for the Visual Arts, 919 Broadway When: Today through Nov. 2 Admission: $10 for adults, $7 for college students, seniors and active military, free for Frist Center members and visitors ages 18 and younger By

Peter Cooper

|