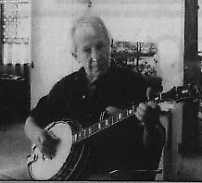

Earl Scruggs is among the most affable of revolutionaries. He smiles often, and speaks more softly and slowly than his hyper-speed banjo picking might suggest. Even today, sitting in his living room and playing a few songs with friend and fellow musician Marty Stuart, the 76-year-old's banjo style is as frenetic and improbable a triumph as a hummingbird's flight. Earl Scruggs is among the most affable of revolutionaries. He smiles often, and speaks more softly and slowly than his hyper-speed banjo picking might suggest. Even today, sitting in his living room and playing a few songs with friend and fellow musician Marty Stuart, the 76-year-old's banjo style is as frenetic and improbable a triumph as a hummingbird's flight.

That style comprised, in fact, the first of Scruggs' revolutions. Historians argue about whether he invented the now-commonplace method of striking the banjo strings with three fingers, one at a time, creating a succession of vibrations that clattered and rolled like the trains that traveled through his native North Carolina hills on the way to Spartanburg. But, whether inventor or perfecter, he certainly brought that technique (now called "Scruggs' Style") over the Appalachian mountains and into the band of one Bill Monroe. He joined Monroe's Bluegrass Boys 55 years ago, setting off a series of events that led to Monroe's deification as Father of Bluegrass Music, to the decline of the now antiquated banjo style known as "frailing," to the formation of Flatt and Scruggs (a duo with Lester Flatt that became the most famous bluegrass band in the world) in 1948, and ultimately to a second, equally important, revolution. Only the next revolution was not merely an upheaval of the status quo. It was also a rotation, a completion of a cycle: revolution like the turning of a wheel. "He was the man who melted walls," Stuart said. "And he did it without saying three words." Stuart was speaking of the folk boom, a time when America's roots music forms were rediscovered and redistributed, passed to a new generation. Much of Nashville's music community saw the boom as a detestable occurrence, a second whack to knees still sore from the bruising blows dealt by rock 'n' roll. And at least rock had a proper Southern upbringing. Folk was Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, communism and flag burning. As the Vietnam conflict raged, the line between country and folk became a political marker. "Well, I didn't look at it from a political view," Scruggs said, "And I thought Joan Baez had one of the best voices of anybody I'd ever heard sing." Like Arkansas native Johnny Cash, Scruggs reached out rather than recoiled. That decision alienated some fans but allowed him to reach a new generation of listeners. It also laid groundwork for the cross-pollinations that birthed country-rock. "Look at this," said Louise Scruggs, Earl's wife and his manager since 1955. "This is the first record Earl ever bought." Louise cradled an original 78 rpm copy of Merle Travis' Folk Songs of the Hills. "Folk songs," she said. Indeed, the recorded history of folk music is the recorded history of pre-1950's country music. The Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, the Fruit Jar Drinkers, the Gully Jumpers and others were folk acts. So when the Newport Folk Festival offered Scruggs and his banjo a slot, the concept was pleasing. His acceptance of that offer began a domino effect that led to banjos, Dobros and fiddles appearing in a slew of interesting places. "The first time I did the Newport Folk Festival, Lester didn't care nothing about it," Earl said. "He didn't go, but I went up there. I'd never been around anything like that, where they just went strictly to hear a song and it didn't have to be put on like a country show." From Scruggs' Newport appearance came a Flatt and Scruggs booking at Hollywood folk club The Ash Grove, where a television producer heard the duo and asked them to appear on The Beverly Hillbillies show. "One thing will lead to another in your life," Earl said. Already immensely popular due to their Martha White Flour-sponsored morning radio shows on WSM, their Grand Ole Opry appearances and their syndicated television series, Flatt and Scruggs had a No. 1 country single in 1962's Hillbillies' theme, The Ballad of Jed Clampett. Around this same time, New York Times writer Robert Shelton told Louise about a young Greenwich Village folk singer named Bob Dylan. "I had the first Bob Dylan record before anybody in Nashville," she said. "Shelton had Columbia Records send me a copy before it even went into the stores. I ended up with every album he ever recorded." She immediately shared the record with her husband.

"Instead of your basic hillbilly head shot, this was art," said Stuart, who not only is one of Nashville's best entertainers/musicians but also is a noted historian and enthusiast of all things traditional and musical. "You could put their album covers alongside any of the jazz covers of the day. It presented Flatt and Scruggs in a different way." A display of Allen's illustrations opens Thursday at the Ryman, the morning after Scruggs, Stuart and others perform a Great American Folk Boom concert. By the mid-1960s, Flatt and Scruggs were performing regularly at colleges and folk festivals. "The audiences just ate it up," said Bob Neuwirth, a folk singer and contemporary of Baez and Dylan (he also served as Dylan's tour manager). "People were in awe of it because it was so beautiful. Bluegrass was infectious and Flatt and Scruggs got a leg up on everybody because of Scruggs' banjo: Nobody had heard playing that smooth and that complex." Washington, D.C., progressive bluegrass band The Country Gentlemen were likely the first in the genre to play a folk boom-inspired college show (at Antioch College in Ohio), but Flatt and Scruggs' popularity marked their appearances as historically important and culturally innovative. "They were bringing this music to a wider audience," said Dobro virtuoso Mike Auldridge, a bluegrass luminary and member of The Seldom Scene from 1971 through 1996. "When I was a kid, Scruggs was like a god to me and later on he was the architect of this bridge between different kinds of music." But while Flatt enjoyed playing at Carnegie Hall and at lucrative college gigs, he was not enamored of Dylan, Baez or the peace movement that was interwoven with the festival scene. To Lester's chagrin, Flatt and Scruggs recorded several Dylan songs including Like A Rolling Stone and, incredibly, Rain Day Women #13 & 35 (with the tag line, "Everybody must get stoned"). Things got strange. Flatt and Scruggs and their Foggy Mountain Boys played the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, braving a psychedelic light show that proved discombobulating for Earl. "You'd fall if you wasn't careful," he said, "I almost lost my balance." Early in 1969, with Scruggs wanting to further expand the group's sound and repertoire and Flatt wanting to retain a more traditional approach, the legendary duo disbanded. Flatt went on to form The Nashville Grass and Scruggs played with his sons in the band The Scruggs Review, an ensemble that further blurred the lines between folk, rock and bluegrass. Stuart joined Flatt's band before he turned 14. "I was living at Lester's house and a documentary aired that had footage of Earl playing at a peace rally in Washington," Stuart said. "Flatt didn't get it at all. He thought Earl had sold out and become a communist. "Lester also used to say, 'I ain't got nothing against Bob Dylan, but he just don't write our kind of music,' " Stuart remembered. According to Louise, Scruggs has now recorded 29 Dylan songs. "I think it's ridiculous when people talk about who's real bluegrass and who's not," Louise said pointing to similar discussions surrounding Alison Krauss. "Music's music. Enjoy it."

"We got 70 something college gigs off that one show,"Stuart said. "The college kids would show up just to see what was going on, then they'd fall in love with the music and didn't even know why. That's still happening at places like the Telluride festival in Colorado." Indeed, it's still happening at a lot of places and for a lot of different reasons, not the least of which was that Earl Scruggs played three-fingered banjo regardless of whether writers and listeners dubbed his music country, bluegrass or folk. "It started out all folk music," Scruggs said, citing Opry founder George D. Hay's penchant for calling Opry music "folk music" and thinking back to the first record he purchased, Folk Songs of the Hills by country guitar picker Merle Travis. For Scruggs, then, the folk boom was the completion of a revolution, a circling back to his own roots, to a time when there was no such thing as bluegrass. Earl Scruggs took the banjo to places it had never been, then insisted that the music he helped create was a branch on a tree, not a forest unto itself. "What Earl has done will live forever and it's a remnant of the original vision of our music," Stuart said, "It's folk. It was for the folks." By Peter Cooper |

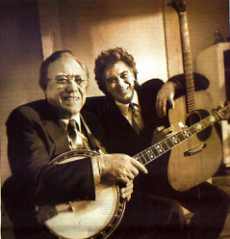

"He [Dylan] wrote some real deep-thinking type songs," Earl said. "A lot of them told a message. I have to give Louise credit for getting us directed into some of that stuff." Louise was a visionary in many ways, and she sought different avenues to increase the band's popularity. After artist Thomas Allen's (shown left in a photo taken by Marty) portrait of Flatt and Scruggs appeared in Esquire magazine, she suggested the artwork be used as the cover of 1961's Foggy Mountain Banjo album. That album was the first of 17 to feature Allen's work.

"He [Dylan] wrote some real deep-thinking type songs," Earl said. "A lot of them told a message. I have to give Louise credit for getting us directed into some of that stuff." Louise was a visionary in many ways, and she sought different avenues to increase the band's popularity. After artist Thomas Allen's (shown left in a photo taken by Marty) portrait of Flatt and Scruggs appeared in Esquire magazine, she suggested the artwork be used as the cover of 1961's Foggy Mountain Banjo album. That album was the first of 17 to feature Allen's work. After the breakup, Flatt eventually returned to the college circuit as well, forging a new audience for his own music in his final decade (he died in 1979). Stuart remembers the Nashville Grass sharing a bill with Kool and the Gang at a college showcase in Cincinnati.

After the breakup, Flatt eventually returned to the college circuit as well, forging a new audience for his own music in his final decade (he died in 1979). Stuart remembers the Nashville Grass sharing a bill with Kool and the Gang at a college showcase in Cincinnati.