July 4, 1997, p.m. Somewhere in Virginia July 4, 1997, p.m. Somewhere in Virginia

The bulletin board in the front lounge of my tour bus reads "Underground Twang Tour. Tonight. Dublin, VA. Showtime 8:15." Judging by the intensity of the rain that's pouring out of the black sky and the lightning that's flashing and occasionally smacking down, God has other plans. His big light show is going to lay waste to the fireworks spectacular that's planned to explode at the end of our Dublin show (if there is a show). My band--the Rock and Roll Cowboys--and I are glued to the television in the bus as CNN brings us live pictures from Mars. "Where are we going after we leave here?" I ask the band. About seven years ago, I lost all sense of where I might be at any given moment. I'm told tomorrow's show is in Lula, Mississippi. We'll be performing at some cottonfield casino in a town off Highway 61, a few miles south of Memphis. As we start discussing the joys of Memphis, the lightning stops, the rain ceases, and the clouds roll back. "Maybe it's a sign," I say. "Why don't we spend the day in Memphis?" It's time for some fun. For the past ten weeks, we've been knocking off one-nighters like a golfer hitting buckets full of balls. The workload has severely outweighed the fun factor. Memphis can't fix us, but it can help. Memphis is one of my favorite towns. I've been lifted to the foot of the cross there, and I've stood close enough to the devil to smell his rotten breath. You have to enter Memphis with caution--or else it will slide right out from under you. As the word comes down that the Dublin show is on, we head for our stage wear only after unanimously agreeing to visit Memphis. Just talking about it provides us with the spark we need for giving our rain-soaked Dublin fans a star-spangled show. After the show, we vanish onto Interstate 81 South and I wish myself a happy Fourth of July. I then reflect on a show we played in Minnesota on a previous Fourth--we were the closing act for a wrestling match. I thank God for not having to do that again and go to bed. The last thing I think about before falling asleep is how good it is going to be to wake up in Memphisto. July 5, 1997, a.m. Downtown Memphis. My bass player, Steve Arnold--a Memphis native--and I try to come to life as we watch the new day unfold. Steve says, "It's good to be home." Home in Memphis for me is 706 Union Avenue. That's Sun Studio. Any time I'm in town, that's where I go. Going there gives me the same feeling as going to church. As we pull into the parking lot to set up camp, I am unaware that it was forty-three years ago to the day that Elvis dropped by here and recorded "That's All Right, Mama." The last time I was here was in early fall. The Cowboys and I had come to record some demos of songs I'd written. We were having fun and making music when a call came from Bill Monroe's manager. He'd called to tell me that Bill had just passed away and to ask if I would sing and play at the funeral. One minute were playing in the same studio where Elvis had recorded Monroe's "Blue Moon of Kentucky," and a minute later, I was leveled by sad news. I called time-out and took a walk. Bill Monroe was my friend and one of the first musical inspirations of my life. When I was twelve, I saw him for the first time at one of his concerts and, after the show, I asked him for his autograph. He handed me his mandolin pick and told me to use it. Every day I carried that pick with me to school. Later, I got a mandolin and listened to his records over and over and learned how to play using that pick. Since then, he'd been a big part of my life and not having him around was going to take some getting used to. When you lose somebody like Bill Monroe, your world shifts. As I walked the back streets of Memphis looking for some peace, the only thing that came to me were some words for a song for him:

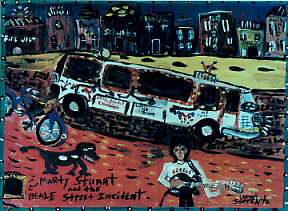

I finished the song in about an hour, then took it back to Sun and played it for the band. We recorded it right there. I listened to the playback, then packed my mandolin and headed home to Nashville. As I was leaving Memphis that time, I thought to myself, This town doesn't mind taking it away from you but, in the long run, it always gives you back a little more than it takes. This rumination drifted away when I heard Roger Miller come across the AM band of my car radio. He sang "The Last Word in Lonesome is Me" and then he too disappeared. The fluorescent lights on a billboard advertising Graceland were either blinking or winking at me as I drove past. I made myself a promise: The next time I'm in Memphis, I'm going to Graceland to visit Elvis' gold lamé suit. Any self-respecting son of the South knows that Elvis is, and will always be, our main cat. I always come back around to the sad feeling that he should still be here among us other than in spirit, and I'd be a liar if I said that I don't take pleasure in admiring his possessions. But what good are a king's possessions when he's not around to enjoy them? Thanks to Louisiana's former Governor Huey P. Long, all of us Southern boys have the right to believe that every man's a king. I thought, Okay, if I'm a king, what are some of my possessions? I've had stars in the heavens as well as children that aren't mine, named after me. Cars, horses, a parrot, a malt in a country music-themed restaurant in Hollywood, a Martin guitar, a street trolley in Nashville, and a country music road in my hometown all bear my name. Treasures, no doubt, but then there are the more personal things, like my country music memorabilia collection that's touring across America this summer, and my dog, my house, my guitar, my jeep and Geronimo's autograph. All mean a lot to me. But one of my most treasured possessions is my bicycle. My friend and manager, Bonnie Garner, bought it for me as a birthday present last year. It's the first one I've had since I was a kid. I keep it underneath my bus, and I can't tell you the joy that it's brought me for the past year-and-a-half. I've ridden it--a Trek ten-speed--all over America's back streets, main roads, and town squares. It's my ticket to freedom. Today is no different. It's a perfect morning for a bike ride: there's not a cloud in the sky, the air is fresh, Memphis is barely awake, and I can't wait to tour the town. I leave Sun Studio and take off down Union Avenue in search of nothing in particular. Before ten a.m., I tour Union, Madison and Poplar Avenues, and Main Street. But no trip to Memphis is complete without a visit to the Peabody Hotel. So I scoot over there and have my bike valet-parked before I go inside to call Earl Scruggs for the King of Bluegrass Jimmy Martin's telephone number. Jimmy left a panicky message on my code-a-phone yesterday. He said he needed some new white boots to replace the pair that he'd given me for my touring memorabilia exhibit. I can understand why they would be hard to replace. They are state-of-the-art white ankle boots made by Acme, with nylon zippers up the side. King Jimmy had them customized with gold tips and had an assortment of red and green rhinestones glued on the toes. His message said, "Me and Pat Boone always wore white on our feet. I'm concerned that my fans are upset with me for not wearing my white boots. Them light brown ones I've been wearing ain't gittin' it! Now you've got to help me find another pair." Anyone who knows anything about fashion knows that downtown Memphis is the place for flashy clothes. Let's say you have a red 1978 Fleetwood Cadillac with wide whitewall-tires, gold-spoke wheels, a glow-in-the-dark hood ornament and a neon-light package underneath the chassis to complement your customized license plate and tinted windows. If you need a suit, shoes, shades, hat or other accessories to complete your ride, Main Street in Memphis is the place to shop. Just a moment ago, I spotted a pair of while snakeskin ankle boots with Cuban heels on sale for $69.98 in the window of Discount Sammy's men's shop at 101 South Main. This might be what King Jimmy is looking for. But all I get is Jimmy's answering service. I enjoy the living-room atmosphere of the Peabody lobby a little more before claiming my bicycle. It hurts me to admit that my two-wheeler doesn't quite have the presence that the stretch limousine parked in front of me has. Although a bicycle is definitely not a star machine, it's a good way to gauge your charisma. You think you're a star? Get a bicycle and see. The head bellman laughs when he sees whose bicycle it is. Then he tells the young man that delivers it not to accept my tip. He says, "Mr. Stuart has done hit on hard times. I remember when he used to pull in here in a car. He even had Jerry Lee Lewis bring him here one morning about three a.m. Then he got a bus. Then two buses. Now look at the boy--he's down to a bicycle. Let him keep that dollar. He might need something to eat." He shakes my hand and tells me when I get something with a door on it to be sure to come back so he can open it for me, and to remember him on my way up. I high-five the whole staff and take a left turn out of the parking lot toward Beale Street. When I make Beale, I see B.B. King's nightclub and the Rum Boogie Cafe. I flash back on some reckless nights and unmentionable sights from days gone by. The smell of barbecue makes its way through the air. I notice the clock on the street reads 10:35 a.m. The shops begin opening slowly. I can sense the effects of last night all over everybody. I stop to admire my favorite folk artist Lamar Sorrento's painting of Slim Harpo in a store window. Music blasts from the restaurants and storefronts along the street. In the span of three minutes, I am serenaded by Robert Johnson, Sam and Dave, Ma Rainey, Elvis Presley, and B.B. King. It's a reminder of the difference in Memphis' music and Nashville's. In my star-making hometown of Nashville, we should and could serve up visitors with a twenty-four-hours-a-day smorgasbord of world-class music. Instead, our guests along Demonbreun Street are treated to karaoke cowboys and cowgirls singing along to pre-recorded, watered-down country music. In Memphis, you get the pure musical morphine. This city hasn't had a hit in a while, but it will. Until that happens, Memphis' musical past is proof that pure soul will sustain you. It's better than money in the bank. Along about where a historical landmark sign for Rufus Thomas stands, I think about Bonnie. She is thoroughly convinced that the month of July is a curse on her life. She can list a string of earth-shattering events reaching from now to deep in her past that have occurred in July. I know that if she had her way, July would find itself in the trashcan alongside daylight savings time and taxes. I've tried to tell her to pray it away, will it beyond herself and rise above it but, when it comes to July, Bonnie's skeptic. As I approach A. Schwab's department store, I remember from a previous visit that as you enter you'll find a section for magic potions to your left: oils, herbs, soaps, candles, and incenses to ward off bad luck, evil spirits, and dirty deeds. I decide to run in and buy Bonnie some lighthearted antidotes to July. I park my bicycle at the front door so I can keep my eye on it while I fill my arms with spell-breaker soap, bottles of St. John the Revelator oil, court-case oil, Satan-Be-Gone oil, jinx-remover incense, a pair of pink fuzzy dice stuck on lucky eleven, and some evil-deed incense guaranteed to stop any bad deed that could be done against you by a hand with five fingers. I inquire about black cat bone, and the sales clerk tells me that she is currently sold out but does have black cat eye behind the cash register. It's then that I realize my enthusiasm has edged beyond novelty and touched on the outer realm of black magic and voodoo. I have no business there, so I back away as fast as my rock 'n' roll Baptist soul can fly. While still periodically checking on my wheels at the front door, I pay for my bag of fun, thank the nice clerk, and sign a couple of autographs. When I walk outside, I discover that somebody, in the few minutes my attention has wavered, has stolen my bicycle. I think about going back inside to see if they have any bring-back-my-bicycle oil. There I stand in the middle of Beale Street with a bag full of jinx removers and spell breakers, and somebody has hoodoo'd me out of my bike. A voice inside me says, "Half of the thrill is the art of the deal. And in Memphis, the most solid scams shift like the sand. When you forgot to look, my boy, you were took." And then the wisdom and words of the great bluesman, Sir Lightnin' Hopkins, comes to mind: "Forget about it, 'cause rubber on a wheel is faster than rubber on a heel." I feel like a hick country boy in the middle of a marketplace in some third-world country who's just had his wallet lifted. I run around looking to see if anybody is riding my bike. I ask a woman sitting on a stool in front of a store across the street from Schwab's if she's seen anybody on a bike. She doesn't know what I'm talking about. I walk over to W. C. Handy's statue and start laughing. I remind myself that Memphis is all about magic and, of course, one of the greatest forms of magic is the disappearing act. "Yeah, that's it. I wasn't stolen; it simply disappeared." I walk up the street to the fire station. Fireman Steve Breault looks puzzled and says, "You're...." Before he can finish I say, "That's right, I'm the guy who just has his bicycle stolen on Beale Street." He laughs and says, "Welcome to Memphis!" He helps me locate a bike shop and offers me lunch before lending me his pickup truck to go buy another set of wheels. I drive out to the bike shop in his truck and buy another Trek ten-speed. When I return, I thank Steve for the fine Southern fire department hospitality and then I take off on my new bike toward Sun Studio. All of this commotion and I still make it back in time for a twelve o'clock haircut appointment with my bass player's personal barber, Robin Tucker. Her aunt used to do Priscilla Presley's hair. After the haircut, I drop a few quarters in the jukebox while having lunch at Taylor's Cafe and Gift Shop. Lamar Sorrento comes by with a painting to give me. He orders a glass of lemonade and, by the time we've swapped some yarns, I am out of quarters for the jukebox. I take that as a sign it's time to leave. I tip the waitress who tells me I shouldn't eat things like the cheeseburger I just had, buy a couple of Johnny Cash records, and round up the Rock and Roll Cowboys. We board the bus for Graceland. The gold lamé suit is calling. Nobody in my band has ever been to Graceland. It seems an appropriate topping to an already full Memphis day. We are given a private tour of the mansion and, after a trip through the trophy room, every one of us bows in deference to Elvis. We all agree on two things: Elvis is still the King and we still have a job to do tonight at the Lady Luck Casino in Lula, Mississippi. Casinos are creeping like kudzu toward Memphis, but I know the city can handle anything that comes through its gates. As of now, the city is hanging on by its roots and looking for a hit. I hope when it's deal-cutting time, Memphis doesn't lose any more than a bicycle or two. By Marty Stuart |