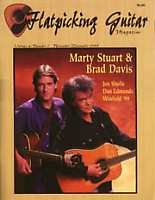

"I am a lonesome pilgrim far from home "I am a lonesome pilgrim far from homeWhat a journey I have known I might be tired and weary but I am strong Pilgrims walk, but not alone" So begins the title cut of Marty Stuart's new MCA release The Pilgrim, and although the story told in this album reveals "the pilgrim" to be a man who has fallen in love with a woman who he doesn't know is married, is subsequently confronted by the woman's husband who then takes his own life in front of the two lovers to prove how much he loves his wife (great bluegrass material!), listening to the opening verse of this song, one can also see Stuart himself as the pilgrim. His musical journey has led him from the bluegrass of Lester Flatt to the traditional music of Doc Watson, roots country of Johnny Cash, and then to contemporary country music stardom with his own band. While the hair, the clothes, and the "hillbilly rock and roll" may appear to be a far cry from Lester's bluegrass, Marty's music cannot really be considered part of the "hot country" of today's "hat and belt buckle" acts either. Stuart has always been somewhat of a rebel in country music, always pushing the envelope, finding his own way, and moving against the mainstream. With The Pilgrim, Stuart also runs against the grain of modern country music, but in a much different vain. Here, he reveals that his heart and soul have never been far away from his roots. In this recording, Stuart not only tells the story of lost love and redemption, he tells the story of his own musical journey within the musical styles, songwriting, instrumentation, and guest artists he brings to this new project. The Pilgrim is a glimpse at the road Stuart has traveled and, in a sense, it is his homecoming. Far From Home Most long-time bluegrass fans will remember Marty Stuart as the mandolin and guitar prodigy who spent seven years beside Lester Flatt in Flatt's band The Nashville Grass. He then went on to play short stints with Vassar Clements and Doc and Merle Watson. Johnny Cash fans will also remember the six years Stuart spent as a member of Cash's band. After leaving Cash, Stuart went out on his own and his musical journey took a turn from bluegrass and roots country. After a few rough years of struggling to find an audience who would accept his mixture of bluegrass, country and rock and roll, Stuart hit the country charts in a big way in 1989 with "Hillbilly Rock." The success of that song set him on the road that he says was "paved" by Los Angeles country-rock acts such as Gram Parsons, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and The Byrds." Although Stuart's music, to the dismay of some bluegrass fans, had definitely taken a turn away from the music of Lester Flatt, the fact is that it worked for him. Over the past decade, Marty Stuart has become one of the most well known, successful, and popular acts in country music. In the minds of hardcore bluegrass fans, Stuart may have strayed "far from home" with his rocking country music, but you can't blame him for following the trail of success. Still, for some bluegrass fans, Stuart's decision to take his music into the realm of "hillbilly rock" may have been a big disappointment. I'll have to admit that I had counted myself as a member of that group up until the time I attended a Marty Stuart concert about a year and a half ago. While the packed arena, loud music, rhinestone outfits, and screaming fans were a far cry from the bluegrass festival atmosphere I was accustomed to, I was greatly impressed with Stuart's effort to incorporate bluegrass and roots country material into his show. Stuart not only included bluegrass tunes (and even a flatpicking medley!) in his act, he spoke to the audience passionately of his great love for the music. It was almost as if Stuart was telling the crowd, "If you like what I do today, then you need to listen to bluegrass because that is where I came from and that is where my heart is." Right then and there my impression of Marty Stuart changed. I stopped thinking of him as someone who had left his roots for the glamour of pop country and began thinking of him as a person who was using his success as a country artist to bring bluegrass and traditional country music to the modern day country fans. Stuart is one of the few artists in the music business who is in the position to introduce bluegrass music to a very large audience and, more importantly, he's doing it. While it was the Marty Stuart show that influenced me to look at Marty from a new perspective, The Pilgrim is what has made me one of his fans. Stuart's decision to include bluegrass and country legends Ralph Stanley, Earl Scruggs, Johnny Cash, Emmylou Harris, Josh Graves and George Jones on this recording certainly adds an element of greatness to the project. However, these legendary voices are not what makes this recording great. It is Stuart's songwriting and the soulful way he puts the words to music which makes this record stand out. Stuart has said that he "likes to write new songs that sound old" and with such great new songs as "Harlan County," "The Pilgrim," "Hobo's Prayer," and "The Observations of a Crow," I think he has hit the mark. When I first heard Ralph Stanley sing "Harlan County," I could have sworn this was an old Stanley Brothers' song that came right out of hills of Clinch Mountain. I was amazed to see that it was written by Marty for this project. When asked about his decision to put together such a unique project, Stuart said, "What I feel like I have done with The Pilgrim is regained my credibility. Not to say that I discount anything that we've done over the past fifteen years, but you back it up to before we had a hit with "Hillbilly Rock," and, man, I tried everything. I tried bluegrass, I tried folk, I tried country, and the first thing that took off was "Hillbilly Rock." So what do you do? You start chasing. You work what works for you. We played for thousands of people, sold lots of records and won lots of awards. But then came a point where I looked around at the state of affairs in country music and it was just disposable pop music. I went over to talk to (Earl) Scruggs about it one day and he said, 'It just don't really turn your crank, does it.' I thought, 'Well put!' " Although Marty Stuart's musical journey has indeed taken him "far from home" in many ways, I get the feeling that home is always where Marty Stuart's heart has been. With The Pilgrim, he definitely lets us know about it. Stuart says, "I read a book called In The Country of Country. It made me really stop and think. The music we are talking about here (in the book) is going to last forever. The kind of records that we are trying to keep up with and make a trend out of (today) are going to be disposable. I thought, 'Well, I am going to stop making records long enough and really make a record.' I took three years off to do that. I wanted it to be an album based around my band to showcase the brilliance of those guys' gifts. I wanted to go back to the heart and soul of the matter and record everything from Ralph Stanley to what we play today." "I think if country music is going to survive and sustain as a credible art form that it has to return to the 'heart and soul' factor. As always, the most promising point of country music's future is the bluegrass pickers. You look at Chris Theile and all of the kids playing fiddle. All of those guys really have it in their hearts. There is a whole new crop of them at any bluegrass festival. If country music does have any future with pickers, bluegrass is where they are going to get them. If you think about it, the most credible players in country music right now came out of bluegrass. So enough said." What a Journey I Have Known Although Marty Stuart is only 41 years old, his musical journey has already been a long one, having now been a professional touring musician for nearly 30 years. When he was a young boy growing up in Philadelphia, Mississippi, Stuart was drawn to the music of Flatt and Scruggs, Johnny Cash and Buck Owens. While his sister and most other kids his age were out buying Beatles albums, Marty distinctly remembers that his first two albums were by Flatt and Scruggs and Johnny Cash. He fronted his own band, the Musical Rangers, starting when he was eight years old. An old set list confirms Marty's love for Flatt and Scruggs, the Carter Family, Johnny Cash, and Buck Owens. Marty's first gig as a touring musician was with the Sullivan Family, a job Marty's friend Carl Jackson helped him get. Jackson's father, Lee, was influential in Marty's early development as a guitar and mandolin player. Marty first met Lester Flatt at the Bean Blossom Festival in 1971. In an article he later wrote for Country Music magazine, Marty said, "The first time I ever saw Lester Flatt in person was at Bill Monroe's Bean Blossom, Indiana festival in 1971. I was 12 years old. I looked at the program and found out what time he was playing, and I stood by his bus to watch him come out. That old bus was a sight. It looked like a rolling billboard, 'Lester Flatt and the Nashville Grass Sponsored by Martha White Flour.' It was a vision in diesel. I had no idea that within the next year I'd be on that bus. That's where I'd spend my teenage years. To this day when I'm asked, 'Where were you raised?,' I say, 'In the back end of Flatt's bus.' " Roland White, who was Lester's mandolin player at the time, recalls how Marty got the job with Lester. "Marty came up to the bus at the festival. I remember that he was very energetic and had a lot to say. He wanted to meet Lester and we got to talking. He said, 'Do you think I could come to Nashville sometime and go out for a weekend show?' I asked, 'What would your parents say?' He assured me that they knew of Lester and wouldn't mind. "I didn't think much more about it until Marty called later and said he wanted to come up. He put his mom on the phone and she said it would be all right. I asked Lester about it. Lester had enjoyed Marty when he met him at Bean Blossom because he was polite and respectful. He said Marty would come on the trip as long as I would be responsible for him." After meeting Lester Flatt and Roland White at Bean Blossom, Marty had spent the entire summer practicing with his friend Carl Jackson and performing with the Sullivan Family. When Jackson was out on the road with Jim and Jesse, Marty would pick with Jackson's father. When school started, Marty was less than enthusiastic about being there after spending the summer doing exactly what he loved. After being suspended from school for reading Country Song Roundup in his history class, Marty decided that school was not for him. Marty recalls that his history teacher slapped the magazine out of his hand and said, "If you get your mind off that garbage and get it on to history, you might make something out of yourself." To which Marty says he humbly replied, "I'm not into readin' about history. I'm into makin' history." Marty then went home and called Roland and asked if he could accompany the band on their Labor Day Weekend trip to a festival in Delaware. In the bus on the way up to the festival, Marty and Roland started picking together. Flatt was impressed with what he heard and asked if Marty would like to come up on the stage during the show and perform a number or two. Roland White recalls, "Lester heard Marty and liked that he had a true, clear voice and was right on. After Marty performed on stage with the band, Lester just loved him. Lester wanted Marty to join the band and said he would make sure that Marty got his schooling." When Marty first moved to Nashville, shortly after his thirteenth birthday, he lived with Roland White. Stuart admits that until he moved in with Roland, he had never heard flatpicking in bluegrass. Roland played some albums and tapes that he had recorded with his brother Clarence and the Kentucky Colonels. Hearing Clarence White play the guitar opened up a whole new world for Marty. Roland began showing Marty some of Clarence's licks and Lester gave Marty the chance to stretch out on the guitar during the shows by allowing him to play lead guitar on a few of the instrumental and vocal numbers. When Roland left the band in 1973 to reunite with Clarence in the New Kentucky Colonels, Marty moved over to fill the mandolin spot. However, Roland remembers telling Marty, "Mandolin playing is fine, but the money is in the guitar. The most popular instrument is the guitar, so that is the way to go. Don't give up the mandolin, but focus on the guitar." Evidently Marty took Roland's advice as he is one of the finest acoustic and electric guitar players in the business. Roland White says, "Marty is one of the people who is the best at playing Clarence's stuff." When Lester Flatt died in 1979, he was still under contract for two more recordings. Marty took this opportunity to produce a tribute album to Flatt and it was during the production of this record that he first met Johnny Cash. Marty's first exposure to Cash had been a television show he had seen when he was only five years old. The sound of Cash singing "Big River" was something that has stayed with Marty his whole life. He says, "The sound of 'Big River,' the sound of his voice and his attitude. That is what drives me." Marty felt that he needed a star on the album. He found Cash's number and gave him a call. When Marty approached Cash and asked him to be involved in the tribute album to Lester Flatt, Cash was very willing to help as he had been on the same bill with Flatt and Scruggs during a number of tours in the 1960s and was a fan of their music. Marty says, "The minute we shook hands, I knew there was something right about it." After Lester died, Marty went on to play with Vassar Clements for a short stint and then played about six months with Doc and Merle Watson. Just as the Doc and Merle tour was winding down, Cash called Stuart and asked him to join his band. Marty was a member of Cash's band from 1980 until 1986. I Might Be Tired and Weary, But I Am Strong After leaving Cash's band in 1986, Stuart hit the road with his Hot Hillbilly Band. After the six-year stint with Cash and having been a sideman his entire professional musical career, it was time to make a move to the front. Marty signed a recording contract with CBS Records and they released the album Marty Stuart in 1986. The first single off the album, "Arlene," made it to the Billboard Top 20 and Marty was nominated for Best New Male Vocalist by the Academy of Country Music. It appeared as if Marty was on his way, but success eluded him. The album did not do well on the charts and CBS decided not to release the follow-up album Let There Be Country (which was later released on Columbia). Audiences at the live shows were also not quite ready for the rock and roll bluegrass bandit. Marty was determined to be different and he was not going to play it safe. He now admits that he "overexaggerated everything at the beginning" in an effort to get himself noticed. With the record contract gone, Marty returned home to Mississippi in order to collect his thoughts and try to decide what to do next. He felt burned out with the music business at the ripe old age of 29. He returned to his roots and once again played with The Sullivans for a while. With The Sullivans he says that he "redisovered the joy of music without pressure." His creative juices began to flow once again. After reaching the lowest point in his career, Marty regained his confidence and went back to Nashville. Convinced that he had had the right idea, he went back with renewed energy. He says, "I knew that I had to keep working at it and struggle. It was all about gutting it out." His determination and strength of resolve has led Marty to the top. He has released four albums that have gone gold, he has had six top ten hit singles and he has won three Grammy Awards. He has written several scores for major motion pictures, hosted his own TV show on TNN and has appeared on albums with The Highwaymen, Neil Young, Emmylou Harris, Johnny Cash, Travis Tritt, Dolly Parton, George Jones, Doc Watson, Pam Tillis, June Carter Cash, Randy Scruggs, and Wynonna Judd. He was the subject of a Marvel Comics special edition, has had a streetcar in Nashville named after him, a street in Philadelphia, Mississippi named after him, was presented with the Mayor's Metronome Award by the mayor of Nashville and was given the Mississippi Governor's Award. Pilgrims Walk, But Not Alone While Marty's newest project, The Pilgrim, has continued to receive rave reviews since its June 1999 release, it is not a project that is Stuart's alone. We have already mentioned the all-star cast that Stuart brought into the studio to help him with this recording (Earl Scruggs, Ralph Stanley & the Clinch Mountain Boys, Johnny Cash, Emmylou Harris, George Jones, Pam Tillis, Josh Graves, Mike Bub, and Stuart Duncan), but the other important group which helped to make this album great are the members of Stuart's band, The Rock and Roll Cowboys: Steve Arnold (bass), Gary Hogue (steel guitar), Gregg Stocki (drums) and Brad Davis (vocals, electric guitar and acoustic guitar). In producing The Pilgrim, Stuart once again went against the grain in Nashville and used his own road band instead of session musicians. Having been a sideman for the first fifteen years of his career, Stuart can appreciate that role and thus knows how to take care of the members of his band. Brad Davis has been the guitar player in Marty's band for nearly ten years now and says, "Marty's band is one of the few real creative arenas in Nashville. Although he is the boss, he allows us to be creative and expressive without restrictions. He allows the band to be up front with him on stage and I think he feels most comfortable with that......more than he would be if we were behind him. I think he is most comfortable with that because he was a sideman for so long. He also knows how to take care of us, for instance, when Fender approached him about the Marty Stuart Signature Guitar, Marty made sure tha each member of the band got a new Fender guitar. He takes good care of us." When asked about his involvement in The Pilgrim project, Davis said, "On many projects in the past, Marty stood up for us in front of the record company and demanded that we be used on his record where they wanted to use the "A-team" session players. On The Pilgrim, it was his concept from the start. He was the captain at the helm from its infancy and he made sure that we were included on that one every step of the way." When Stuart hired Davis nearly nine years ago, Brad says that there were many great Tele players at the "cattle call," but he got the job because he came from bluegrass. At a recent show, Stuart introduced Davis as his "brother" because he said that they had both come from bluegrass and bluegrass players always stayed together like brothers. If that is the case, with players like Brad Davis, Earl Scruggs, Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys, Josh Graves, Stuart Duncan, and Mike Bub on The Pilgrim, Marty has chosen not to walk alone but to have many of his "brothers" come along for the journey. The Interview I read that the first guitar you had was a Silvertone electric that you bought when you were eight years old? Well, the very first guitar I had was a little cardboard cowboy guitar. But the first guitar I bought that would tune was the Silvertone. I know that you love Fender guitars. When did you get your first Fender? When I first started playing, me and my two buddies in the neighborhood had a band, The Musical Rangers. We were just as dead wrong then as we are now. We were outsiders then because we were booked to play at a high school prom and they were expecting top-forty hits from 1970 or '71, whenever it was. We were playing "Wreck of the Old 97," "Tiger by the Tail" and "Wildwood Flower." It wasn't exactly what they wre expecting. At that time, to me, to own a Fender guitar like Luther Perkins, Roy Nichols, Buck Owens, or Don Rich played, was the ultimate thing that anybody could ever want. My mom worked at a bank and I said, "Mom, I want to have an appointment with you." She laughed and said, "OK." I said, "I would like to borrow the money to buy an electric guitar." She and my dad co-signed with me and said, "This is your first lesson in responsibility. You have to pay us back. You can have anything you want to, but you have to pay us back." The closest dealer was in Kosciusko, Mississippi. I went up there and could not believe what I saw. The entire wall was plastered with vintage Fenders, new Fenders, you name it. There was a '54 Strat, an early telecaster -- they even had a Broadcaster there. But the one I picked was a brand new Fender Jaguar because it had the most knobs on it. That was the worst guitar they ever made. That was after you had the Silvertone? I first had a Silvertone acoustic and then an old Craftsman electric guitar. Then a Japanese guitar. The first Fender I had was the one I borrowed from a cousin and he needed it back, so that is when I went and got the Jaguar. As far as learning how to play the guitar, what was the process there? The thing that I loved was country music and bluegrass. The first two albums I ever had was a Johnny Cash record and a Flatt and Scruggs record. So the thing I had going for me was that most of their music was three chord music. I had the kind of record player that you could slow down. I learned the chords to the songs that way. There was a hardware store in my hometown called Turner Hardware that had a pretty good selection of off-brand instruments. They had electric guitars, mandolins, fiddles. There was an electric mandolin. A Kent brand. It was a sunburst and it looked cool. I would go up there after school and play it. I went in there one day and it was gone. I said, "What happened to the mandolin?" They said a guy named Joe Crenshaw brought it. I knew Joe Crenshaw because he worked with my daddy at the factory. Joe was a good ole country boy. Joe bought the mandolin and, of course, they gave him a chord, but he failed to realize that he needed an amplifier. He went home and couldn't get any sound out of it, so he cut the end off the plug and stuck it in the wall. When he hit the mandolin, it knocked him through the wall. He came over to the house and said, "John you've got to give me something for this mandolin because it about killed me." That was my first mandolin. About the same time that I got that, I had bought a couple of Bill Monroe records and was discovering bluegrass beyond Flatt and Scruggs. There was an incredible player named Carl Jackson that lived about 20 miles away in Louisville. He and his dad would come down to my hometown and play with a gospel group called the Page Family. I was introduced to Carl and his dad sold me my first little Gibson A-40 mandolin. This is when I fell head-over-heels in love with bluegrass and forgot about playing electric music for a long time. Who taught you those first three chords? My buddy's mom, Jane Hodgins, showed me G. C., and D and that got me through "Tiger By The Tail." The songs we were playing were very simple. When I got Monroe's thing, I got an old 78 at a little community church and then Carl Jackson's dad, Lee Jackson, gave me an old Harmony album called the Original Sound of Bluegrass that contained cuts off all of those Columbia records that Lester and Earl and Chubby Wise had made with Bill. There was a song, "Will You Be Loving Another Man" on there. The way Monroe started it off was to chord the D string and let the A and E ring. As long as everything was in A, I was sailing. I really learned how to play the mandolin off that one album. I would sit by the record player and try and try and try. I couldn't play an F very well and I was having trouble with minor keys. I was getting so frustrated that I wanted to give it up and quit. I tried so hard and it just wouldn't come. We went to church one Sunday night and I came home and stated to go to bed, but before I did, I picked up my mandolin and, all of a sudden, it was there. I can't explain it other than God just handed it to me. That is when I really fell in love with bluegrass. Right after I discovered bluegrass festivals and it was crazy from there. When you started to play with The Sullivans, were you playing guitar or mandolin? I played mandolin because Carl was playing guitar. Carl got me my job with The Sullivans. He introduced me to Enoch. At that time, for some reason, someone stuck a fiddle in my hand and me and Carl and Enoch would play some three fiddle stuff and, boy, I was sour. I think I caused some people to join the church! Did you and Carl pick a lot together outside of doing the shows? It seemed like we played together all of the time. Before Carl worked with The Sullivans, he had a job with Jim and Jesse at the Opry. He would come back to Mississippi during the week and I would go and hang out with them. He and his dad were so patient. They would sit and teach me tunes. His dad was especially great at it. He had already schooled Carl and Carl was such a wiz that he just took off naturally. Did Carl's dad play guitar? He was a good guitar player and he liked to sing, and he played pretty good mandolin. He was one of those guys who could do a little bit of everything. He took so much time with me that one summer, the summer of 1970, and gave me the encouragement that I needed. We couldn't wait for Carl to get home. What would you say you learned about the guitar from Lester? Lester was really an ensemble player. He was a good band player. You take what he did on "Six White Horses," or the quartet numbers -- Lester was not the kind of player that would jump out at you like a Doc Watson or Tony Ride, but if he quit playing, you really missed it -- which is the mark of a great ensemble player. He had what I call the pure old-timey Tennessee lick. He was brillant at backing up fiddle tunes. He was such a great singer and it was a perfect blend between what he would sing and how he would accompany it. He really knew how to back it up. At that early age, were you picking up on that stuff and incorporate it into your own playing? I knew that before I ever met him. When I sat down beside him on the bus when Roland invited me to come up and ride along with them for the weekend, Lester agreed to it, but he didn't know who I was. I'm thirteen years old and I sit down beside him and start talking to him about recordings he had done with Charlie Monroe, the kind of guitar he played, the way he wore his hat, the color tie he wore.....he looked at me like I was a Martian. We were friends 20 miles out of town. When did you first hear lead flatpicking guitar? I had always loved Maybelle's playing and I had the Flatt and Scruggs, Songs of the Carter Family record. I realized that Earl's playing fit very well with that and I was aware that Doc and Earl and Lester had made a record. But to answer your question straight out, I had never heard flatpicking until I moved in with Roland. Roland had an album cover on his wall, Appalachian Swing. I said, "Was that a band you were in?" He said,"Yea, it was my brothers and Billy Ray and LeRoy." I said, "Let me hear some of that music." The first time I heard Clarence play, my world went from black and white to technicolor. I said, "My God, that is great." At the time, he was working with the Byrds so I asked to hear some of his electric stuff and that blew my mind as well. So, the three-fingered stuff we could do on the hymns, that fit really well. But there came a point where I was really trying to figure out how I could flatpick inside of Lester's band and, in truth, it really didn't fit. And when I look back on it, I have to be very honest, the style of mandolin I was playing really didn't fit either. It wasn't a flatpicking and mandolin-based band. It was more the style of Curly Seckler and Everett Lilly, which I love. Now, when I play with Earl, I try to play something like that instead of something that is very notey. I got into bending strings and I listen to it now and say, "Oh, I shouldn't have done that." To me, with a band like Lester's or Monroe's or the Stanley's, that sound is there and it really don't need improving. I was trying to fit a square peg into a round hole sometimes. I was young and trying to find myself. But if I had to do over again, I probably would have played a whole lot more traditional. Were you playing the three-finger guitar leads on the gospel tunes? When Roland left the band to play with Clarence in the New Kentucky Colonels, I moved in with Lester because my mom and dad hadn't moved up here yet. That old guitar that has the L-5 in it was laying in the corner of Lester's office and it didn't have any strings on it. I adopted that guitar and got back there in my bedroom and started learning those licks as close as I could to the way Earl did them. We recorded an album called Flatt Gospel and that is the first time I played that kind of stuff for real. After I did that, I got the confidence and kept up with it. Did you ever do any flatpicking in Lester's band? Yes, Lester let me do what I wanted to do. We did a tune called, "You Won't Be Satisfied That Way" on some of the radio shows. He would also turn me loose to play a guitar tune. We usually did something like "I Don't Love Nobody" or "Lost Indian." Had you ever tried to play lead on the acoustic guitar before you heard Clarence? Not really. I was still into the Ventures and Luther Perkins and that kind of stuff. I would do that single-string stuff on the electric guitar. But I got so involved in Clarence and, I'll tell you the truth about it, Roland can play exactly like Clarence. He can sit down and show you lick for lick what Clarence was up to. He would spend hours with me. Then I started finding all of these bootleg tapes from the Ash Grove. Clarence fans and Kentucky Colonels fans would send them to me. After Roland left Lester's band, it wasn't no time till Clarence got killed. Roland was in and out of Nashville a lot more after that happened and we would go out and play a lot of the same old Places -- the Station Inn, the Pickin' Parlor. I was really into my Clarence White mode then -- I mean trying hard for it. That is when I really fell in love with the art of flatpicking. Did you ever get to pick with Clarence? I met Clarence a couple of times but we never did get to sit down and really play. I was in awe of Clarence. He had a lot of star power and mystic about him. He was definitely a rock star, so I pretty much kept my mouth shut and watched. I read, in relation to Clarence and Buddy Holly, you had talked about something you called "lead acoustic rhythm." Could you describe that? It really is some of my favorite playing. Earl's technique probably ain't what Bela Fleck's is, but there is a soul about it. Earl can get more out of three notes than most people get out of a whole evening. Clarence was the same way. He could syncopate and he was rhythm oriented. With the Cash band, when we would strip it down and do a Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Three thing, there wasn't a lot of music, but when you got into the rhythm side of it, it got huge. And the less you played, the bigger it got. Luther Perkins was the same way. Buddy Holly, too. I think they did it out of necessity because they didn't have a guy to play rhythm. When you only got one guitar player and it comes time for that guy to take a solo, something drops out. If there is any way in the world you can keep it rocking with a good lead and still have the rhythm, you really have something. Maybelle was the queen of that and, of course, the finger pickers do it. The older I get, the more I believe in what Johnny Lee Hooker told me one time. He said, "Son, fancy chords don't mean shit. Get you one note and make it feel good." I told that to Tom Petty and he said, "He's right!" That is the way I see it anymore. It is like, if you can find a feeling, I would just as soon have five notes that rung the bell than 150 that were all technique. When you talk about lead rhythm, you are talking about playing a lead break, but not having the rhythm drop out? That's right. Buddy Holly's "Peggy Sue" is a good example. The way Earl plays "You Are My Flower." The way Maybelle played it, especially that autoharp thing. I think she called it the "Carter scratch." Doc is also great at it. Doc and Merle were pure masters of it. You have also stated that in order to become a good lead player, on acoustic or electric, that you thought it was a good idea to start out playing rhythm on the acoustic guitar. Can you elaborate on that? Butch Robbins taught me that. Butch Robbins was recording an album one time and he invited me to come play on it. I thought I was going to get to go and play a bunch of hot licks. Butch said, "No, I want you to play rhythm." I said, "Rhythm!" He said, "Marty, you have to learn how to play rhythm before you can play lead." It hurt my feelings, but about two songs in, I thought, "He is right!" Once you can hold a band together with the glue, it don't matter after that. I think that without rhythm, lead suffers. And without lead, rhythm suffers. It takes it all. But rhythm is so important. Do you think that a guitar player should become a good solid rhythm player before they learn how to play a note of lead? Well, it don't hurt. B.B. King is totally a lead man, but people like him have a great rhythm section. But if you are going to be a well rounded guitar player, rhythm is essential. If you can handle rhythm, you can move on out with your lead. You said that the period of time you spent with Doc was "the most fun I've had on stage" and "that I was able to express myself." Did Doc tell you to do whatever you wanted? The music set the atmosphere for that. With Lester it was very restrictive. We had a legend band to live up to. The arrangements were set and people expected to hear them a certain way and, like I said, I wish I could have stuck closer to it. But with Doc and Merle, it was more like jazz. It was whatever came out that night. Doc had certain things that he did note-for-note every night, but the thing that really kicked me in the butt and spurred me on was Merle. Merle Watson was one of the most brilliant players that I have ever played with. His slide playing on "Spike Driver Blues" was the sweetest thing that ever happened. I loved it when me and Michael Coleman shut up and Doc and Merle would do their thing on a tune like "Shady Grove." It was the best that ever was. Did you mostly play mandolin and fiddle with them? I played mandolin and fiddle and me and Doc would do some dual flatpicking. Before you played with Doc and Merle, you had a short stint with Vassar Clements, didn't you? Vassar was the first gig I had after Lester. You played the electric guitar with Vassar, didn't you? I had just got a B-string bender on a telecaster. Why he hired me, I don't know because I couldn't play a lick. Vassar was into this jazz fusion thing at the time and I was way in over my head. He was very kind to hire me. That must have been a big change going from Lester to jazz fusion? It was weird, but I loved it because it was a different challenge. It made me get on my toes and try hard. I read where you said that in country music today you would like to see the pickers more in the forefront. Are you talking abut instrumentalists in the band stepping out in front like they do in bluegrass? It goes back to bluegrass thinking and jazz thinking. If you go back to all of the great bluegrassers and jazzers, they didn't hog it, they made everybody on the stage shine. When I started my band, my hillbilly band, I thought, "The one thing I am going to do is surround myself with brilliant players who are stylists. Guys that can out play me usually. Like Brad. It has been incredible for the last nine years to watch Brad Davis grow as a player. I was never so proud of him as I was just recently. We played the Grand Ole Opry with Scruggs. Randy couldn't come and play one night and so I asked Brad to fill in. It is pretty intimidating to walk into the Scruggs house if you have never been there. But he walked in there and sat in the circle. I said, "Let's run through what we are going to do tonight." It was "Foggy Mountain Breakdown" or "Flint Hill Special" or one of those kind of tunes. Man, when Brad Davis hit it, he took it to another place that I have never heard guitar sound like in that kind of music. Man, it raised eyebrows all around the room. Earl called me the next day and said, "That boy you got on the guitar is good." So he was endorsed by the master. I have watched Brad grow and grow and grow. I have watched him go from not having a tone to finding a tone electrically that he can call his own. I have watched him acoustically go from being a Tonyt Rice disciple to Brad Davis the guitar player. I have watched him mature and find taste instead of twenty-five licks. If there is a tone in a guitar, he knows how to find it. It has been incredible to watch him grow and he is on his way to being a master. When I heard him play with his bluegrass band at Doc and Merle's festival this year, I was in awe of him. I said, "This boy has got it and gone with it." I saw a whole side of him there that I feel like I am holding back on stage. I have read that you think it is important to be a "tone player." Could you describe that? In country music today, there is a "session tone" that producers require. They bring in ten heads off of different amps and it is what I would call a "rack tone." It all sounds the same. Tone players have a signature tone. I can hear two notes and know that it is Earl Scruggs. I can hear two notes and know that it is Ralph Stanley, or Vassar, or Clarence, or Roland, or Roy Nichols, or Ralph Mooney, or Luther Perkins. It was truly a badge of honor to have a signature tone back in those days and I loved that. Now when you listen to commercial radio, it is hard to pick anybody out. As far as acoustic players, who do you think are tone players? Tony Rice is a fine tone player. There are guys like Scotty Stoneman. I've seen him go through ten fiddles a night and they all sound the same. The tone just lives in his body. Scruggs is that way. He can pick up twenty banjos and they sound the same. I think tone is something that lives in you, but it helps to have an incredible instrument too. You had said that the songs you like to write are "new songs that sound old." On The Pilgrim, I can find several examples of that, namely "Harlan County" and "Hobo's Prayer." Is that what you were going for when you were writing those songs? Not intentionally. I have read that the two events that insprired the new album were your reading In the Country of Country, as you mentioned earlier, and Bill Monroe's death. When we were playing at Bill Monroe's funeral, I looked at Vince Gill, Ricky Skaggs, Stuart Duncan and myself and, without saying a word, I think we all knew that we had a little bit deeper responsibility not to just make corny records and keep up with the trend. For some reason, we knew that we had some business to take care of. I really applaud Skaggs. He is on fire and I am his biggest cheerleader. Something special is just starting to happen in Nashville. There is a line being drawn. You can't quite see it yet, but it is there. And I just want to be on that side of the line. Are you planning on doing anything in the bluegrass world? I just finished producing Jerry and Tammy Sullivan's record. It is on Skaggs Family Records and is coming out this fall. What have you got planned in the future along those lines? I am going to produce Leroy Troy. Leroy Troy thinks that he is Uncle Dave Macon and I ain't going to tell him no different. There are a bunch of boys around Goodlettsville, Tennessee that are hardcore mountain hillbilly music enthusiasts and I love it. Leroy has a deal with Rounder, and so I am going to get to that this fall. He plays banjo truly in the vain of Uncle Dave and Stringbean. He is a young guy who has the soul of a thousand-year-old man. It is pure as mountain moonshine. That is the only kind of music I am into working on right now -- real pure stuff. By Dan Miller |