|

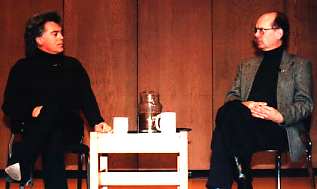

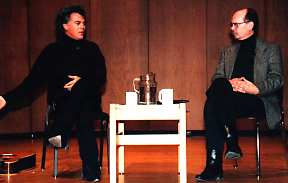

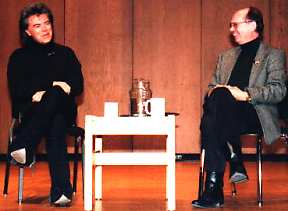

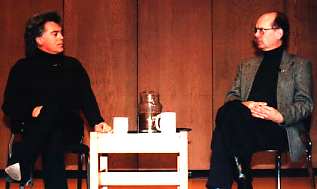

The Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt University in Nashville presented "A Conversation With Marty Stuart" on December 4. Dale Cockrell, Professor of Musicology and American and Southern Studies at the school, was the moderator The Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt University in Nashville presented "A Conversation With Marty Stuart" on December 4. Dale Cockrell, Professor of Musicology and American and Southern Studies at the school, was the moderator

Mr. Cockrell welcomed the small audience and said he tried thinking of someone to invite for the series, "and it took not a matter of seconds for the answer to come to me. And that's Marty Stuart. I thought of all the musicians that I knew around here, none would more embody this thing that we call Southern Music. We talked with the wild idea of calling Marty, and saying........he didn't know me from Adam at the time......of calling him and saying ‘Do you mind coming and speak to us?". I am deeply honored.

"From Mississippi, Marty Stuart was a force in our music even as a boy. He was only 13 when Lester Flatt hired him as the mandolinist in his bluegrass band--a position that he held for six years. He went on from there to back up Vassar Clements, Doc Watson and, for several years, Johnny Cash. 1989 signaled that he was very much his own musician when he released his first recording for MCA, Hillbilly Rock. This album, thankfully, returned some of the rhythmic punch and fun to country music that had been lost over the years. And two years later, Tempted confirmed Marty's stature as one of the rising young stars of country music. The critically acclaimed and highly popular Marty Party Hit Pack in 1995 added new luster, and his complex, richly raw The Pilgrim of 1999 proclaimed new depths to Marty Stuart's music.

"Yet, there's much more to this man than a litany of top ten hits, a list of his Grammy's (three to date), membership in the Grand Ole Opry. Perhaps no musician in Nashville today is as varied in his position of his talents or more a champion of the music. An excellent singer/songwriter who's among Nashville's very best mandolinist and flat-picking guitarist. He's just back from Los Angeles where he's been working on a movie, his second in two years. And the regard of his peers known for his talent has been indicated in part by his election to the Presidency of the County Music Foundation, an association that promotes the industry and, among other things, oversees the Country Music Hall of Fame. "Yet, there's much more to this man than a litany of top ten hits, a list of his Grammy's (three to date), membership in the Grand Ole Opry. Perhaps no musician in Nashville today is as varied in his position of his talents or more a champion of the music. An excellent singer/songwriter who's among Nashville's very best mandolinist and flat-picking guitarist. He's just back from Los Angeles where he's been working on a movie, his second in two years. And the regard of his peers known for his talent has been indicated in part by his election to the Presidency of the County Music Foundation, an association that promotes the industry and, among other things, oversees the Country Music Hall of Fame.

"Marty Stuart is also an historian. Even as a young man, he started collecting the instruments, the clothing, the memorabilia and today he owns probably the largest collection of country music artifacts in the world, some of which will be on display in the new Hall of Fame.

"All this and Marty Stuart still doesn't know where he fits in. And that doesn't bother him. ‘Actually for most of my life, I've not fit in and that is just fine by me.' Well, I thought I had him pegged and then I opened the pages of Oxford American recently and there's Marty Stuart again as a photographer this time. Marty said it well when he suggested that he specializes in diversity. The term ‘renaissance man' is overused but it seems to apply today. It gives me great pleasure and it brings honor to the Blair School of Music to welcome tonight an extraordinary man and an extraordinary musician, Marty Stuart." "All this and Marty Stuart still doesn't know where he fits in. And that doesn't bother him. ‘Actually for most of my life, I've not fit in and that is just fine by me.' Well, I thought I had him pegged and then I opened the pages of Oxford American recently and there's Marty Stuart again as a photographer this time. Marty said it well when he suggested that he specializes in diversity. The term ‘renaissance man' is overused but it seems to apply today. It gives me great pleasure and it brings honor to the Blair School of Music to welcome tonight an extraordinary man and an extraordinary musician, Marty Stuart."

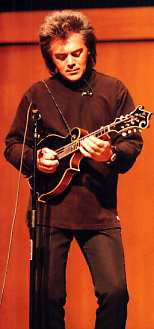

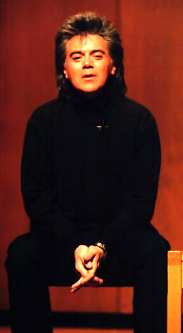

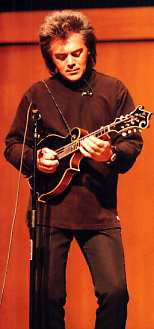

Marty came out with his mandolin, stood in front of the microphone, and picked an instrumental tune in his usual talented way. "That's my way of saying Good Evening and thanks for having me. Dale, thanks for having me at the Blair School and it's my privilege to be part of this program. Because I love the integrity and dignity that it stands for. I understand the theme of the evening is Southern Music and I love Southern Music.

"One of the things that encouraged me the most, that drew me to Nashville was the individuality that everybody brought to the table. I loved, as a kid to sit and watch it on TV and listen on the radio. Everybody brought their stories. They were allowed to be individualists. It was kinda the badge of honor to do that. I didn't know where I fit or where I belonged but I just knew had to come here. I want to be a part of it. Since that time, I've always surrounded myself with champions. Finding young people that had it in their heart too. And one of the most wonderful things about coming here at such a early age is I had access to wit and wisdom of some of the true masters and architects of American music, the cornerstones of our music. I had their phone numbers (laughs) and I used them. When I wanted to learn more about something that somebody had done, Earl Scruggs or Johnny Cash or Merle Haggard and I the opportunity to call ‘em and I took big advantage of that. But one of the beauties along the way........... see, you wonder ‘why did Lester Flatt hire me?' A 13-year old kid from Mississippi. That's the last thing he needed in his life at that point. And he looked just like Eddie Munster (laughs) and who could kinda play the mandolin. But the lesson that I learned is that he passed it on and I thought, ‘ah, that's what it's about, that's how it's done. God gives it to you; you pass it along.' "One of the things that encouraged me the most, that drew me to Nashville was the individuality that everybody brought to the table. I loved, as a kid to sit and watch it on TV and listen on the radio. Everybody brought their stories. They were allowed to be individualists. It was kinda the badge of honor to do that. I didn't know where I fit or where I belonged but I just knew had to come here. I want to be a part of it. Since that time, I've always surrounded myself with champions. Finding young people that had it in their heart too. And one of the most wonderful things about coming here at such a early age is I had access to wit and wisdom of some of the true masters and architects of American music, the cornerstones of our music. I had their phone numbers (laughs) and I used them. When I wanted to learn more about something that somebody had done, Earl Scruggs or Johnny Cash or Merle Haggard and I the opportunity to call ‘em and I took big advantage of that. But one of the beauties along the way........... see, you wonder ‘why did Lester Flatt hire me?' A 13-year old kid from Mississippi. That's the last thing he needed in his life at that point. And he looked just like Eddie Munster (laughs) and who could kinda play the mandolin. But the lesson that I learned is that he passed it on and I thought, ‘ah, that's what it's about, that's how it's done. God gives it to you; you pass it along.'

"This past summer, I was at the Uncle Dave Macon Days in Murfreesboro and I ran across some guys playing music just kinda on the side and they were burning it up. And people were crowded around. Film crews around. There were people with microphones. It looked like a Grateful Dead concert. And these guys are lovin' it. I understand they stopped traffic and had to call Nashville finest to break up a traffic jam on Second Avenue a couple of weeks ago. Before we go any further, I wanna show you what I'm talking about. About people who have it in their hearts. One of the most primitive, yet authentic and wonderful form of American music, American country music especially. Please make welcome my friends, The Old Crow Medicine Show." "This past summer, I was at the Uncle Dave Macon Days in Murfreesboro and I ran across some guys playing music just kinda on the side and they were burning it up. And people were crowded around. Film crews around. There were people with microphones. It looked like a Grateful Dead concert. And these guys are lovin' it. I understand they stopped traffic and had to call Nashville finest to break up a traffic jam on Second Avenue a couple of weeks ago. Before we go any further, I wanna show you what I'm talking about. About people who have it in their hearts. One of the most primitive, yet authentic and wonderful form of American music, American country music especially. Please make welcome my friends, The Old Crow Medicine Show."

The six members of the band came out. Mario and I have seen these guys several times and they are quite entertaining. They are all in their early twenties and they don't play a song newer than 1929 or 1930's (so they say). Most play multiple instruments and their sound is a mixture of bluegrass and Appalachian mountain music. They play a lot of Old Time and Bluegrass Festivals. These guys LOVE what they are doing--and it's nice to know that the music is being kept alive by a group of young men. This time, the guys were dressed up a bit. Suits, jackets--some with hats. Marty had to comment "Most of us have been to the Nashville jail before." The audience roared. Marty and the boys traded quips while the instruments were being tuned. Marty then played mandolin with them on two songs. The Old Crow Medicine show left the stage and went to sit down and catch the rest of the evening's event. The six members of the band came out. Mario and I have seen these guys several times and they are quite entertaining. They are all in their early twenties and they don't play a song newer than 1929 or 1930's (so they say). Most play multiple instruments and their sound is a mixture of bluegrass and Appalachian mountain music. They play a lot of Old Time and Bluegrass Festivals. These guys LOVE what they are doing--and it's nice to know that the music is being kept alive by a group of young men. This time, the guys were dressed up a bit. Suits, jackets--some with hats. Marty had to comment "Most of us have been to the Nashville jail before." The audience roared. Marty and the boys traded quips while the instruments were being tuned. Marty then played mandolin with them on two songs. The Old Crow Medicine show left the stage and went to sit down and catch the rest of the evening's event.

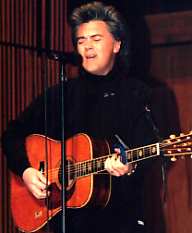

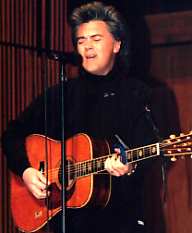

Then Marty picked up his acoustic guitar and started playing and it was out of tune. "Whoa" he said. He proceeded to play "Hard Times and Misery." Then Marty picked up his acoustic guitar and started playing and it was out of tune. "Whoa" he said. He proceeded to play "Hard Times and Misery."

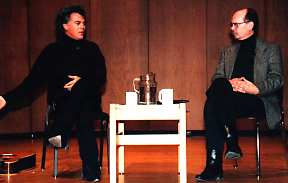

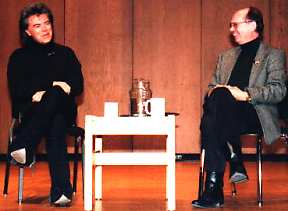

Now it was time for the "Conversation" part of the evening. Marty and Dale Cockrell, the moderator, moved their chairs front and center stage.

Moderator: I think what you saw of Marty Stuart tonight, if you haven't seen him before, when he comes around music, he's on fire.

Marty: I love it.

Moderator: And I've never seen him when he wasn't feeling good inside. I remember at the Ryman this summer before the Earl Scruggs show that you did--the Thomas Allen exhibit you were on, you've guys were going to run through it, Marty Stuart was there, man, he was having the best time. He was playing, he was clapping. You're always there.

Marty: Well, music, pure music, I have no choice. My wife Connie has a saying I really love a lot. She says that "pure music is the cry of the heart." And I love the authenticity of what these guys do. The Old Crow Medicine Show band is just an example. I could have brought people from their age group that play rockabilly music or southern gospel music or blues. But, they're just on file. They're just full of authenticity. I love to baptize them in the same kind of authentic fire. And I love it, I dearly love it. Marty: Well, music, pure music, I have no choice. My wife Connie has a saying I really love a lot. She says that "pure music is the cry of the heart." And I love the authenticity of what these guys do. The Old Crow Medicine Show band is just an example. I could have brought people from their age group that play rockabilly music or southern gospel music or blues. But, they're just on file. They're just full of authenticity. I love to baptize them in the same kind of authentic fire. And I love it, I dearly love it.

Moderator: What are you up to these days?

Marty: Well, I took this year off. I've just come from California. Billy Bob Thornton has got a film called All The Pretty Horses. It's a gorgeous film. I was involved in the score for that. I took some people from Nashville and got some incredible players from the LA scene and we orchestrated a beautiful movie.

Moderator: You're not moving to Los Angeles, are you?

Marty: No. There are no Waffle Houses in Los Angeles. We taped an IMAX film on country music this year. Gotta get around to write songs and making records again. After you make a record like The Pilgrim. The difference between The Pilgrim and all the other records I made is The Pilgrim was purely inspired. It wasn't about playing the game. It wasn't about the charts. It's more about the heart. And I knew it would have commercial ramifications. Probably weren't the greatest but spiritually and soulfully, it stands up. As Johnny Cash made the statement to me, he said "once you make a record like that, you can't go back there." Marty: No. There are no Waffle Houses in Los Angeles. We taped an IMAX film on country music this year. Gotta get around to write songs and making records again. After you make a record like The Pilgrim. The difference between The Pilgrim and all the other records I made is The Pilgrim was purely inspired. It wasn't about playing the game. It wasn't about the charts. It's more about the heart. And I knew it would have commercial ramifications. Probably weren't the greatest but spiritually and soulfully, it stands up. As Johnny Cash made the statement to me, he said "once you make a record like that, you can't go back there."

Moderator: Well, that's going to be my question. What do you do after that?

Marty: You write a cowboy movie. You wait for your heart to fill up, for life to give you some experiences, you go through hard knocks, find some inspiration.

Moderator: Are you on that track?

Marty: Yeah! It's a matter of focusing. And I'm from Mississippi so I find myself in the pine trees down there looking for inspiration. Kinda like what Hank Williams said one time, he said, "Hoss, I don't write ‘em. God writes them. I just hang on to the pen." Marty: Yeah! It's a matter of focusing. And I'm from Mississippi so I find myself in the pine trees down there looking for inspiration. Kinda like what Hank Williams said one time, he said, "Hoss, I don't write ‘em. God writes them. I just hang on to the pen."

Moderator: You mean, really, you're just in some place and there's the song? Is it finished?

Marty: Yeah

Moderator: The whole thing? Text, harmony, the whole thing?

Marty: Yeah. I tend to hear it all. I find that when I go to Mississippi, as broad musically as Nashville is, there's something about going........and I call Nashville home, but something about REALLY going home and getting back under the umbrella. I find out that I can cope with culture of the home state of Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Elvis Presley, Tammy Wynette, and Jimmie Rodgers and many others. Pretty powerful. I have no idea--and it's something I find that I carry this more around. The song that I sang, "Hard Times and Misery," Finally got a royalty check big enough to do something with, I took a vacation in Barbados and wrote a song about hard times and misery.

Moderator: What did Mississippi give to you as a kid or did it give you anything? What was it like growing up in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Moderator: What did Mississippi give to you as a kid or did it give you anything? What was it like growing up in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Marty: I grew up in Philadelphia, Mississippi. I was born in 1958, all I remember the civil rights in 1964, so the summer of 1964 was not the most pleasant summer in my hometown. That's when three civil rights workers were murdered and buried under the dam. So all of a sudden, the life that I'd known, black people we knew were the coolest people in town. They were characters, and they played music. They made you feel good. They made you smile. Loved being on this planet. And all of a sudden, I was told I couldn't go there. I couldn't do that. I couldn't listen to that anymore. Because of the tension.

Moderator: Because of the racial tension?

Marty: There was something about music that made all that disappear. The show that came out of this town was Flatt & Scruggs old television show, Ernest Tubb had a show, and the Grand Ole Opry itself. And I'd be in the living room on Saturday afternoon in front of the TV or at the radio in the evening. Found the situation would kinda disappear. Something about it made the air lighter. . And being from Mississippi from a musical standpoint, we were rained on from Memphis and had the influence New Orleans. There were really no boundaries.

Moderator: Did you grow up in church? Moderator: Did you grow up in church?

Marty: Church was very important. Still is. And I think most of us that come, a lot us in country music, particularly, started out in the church and, as a matter of fact, the first night I ever performed in my life, and my mommy and daddy let me on the road to play music, I went to a little church In Louisiana with a group called The Sullivan Family, they played bluegrass/gospel music. And it was a Pentecostal church and I said, "This is fun." Then about 30 minutes in, somebody pulled out the snakes, and I said, "Ooh, I want my mama?". . But the south has always been, to me, the stories. But there's something about telling stories and how we developed them, how they sent them through generations, generations, how we turned little bitty lies into big ole [unintelligible]. We put words and music to them. It's amazing. Just the richness of the south.

Moderator: Were there honky tonks when you were young? Did you have any experiences with them? Did your mama know?

Marty: No, she didn't know. Hilda Stuart is a card-carrying Baptist. She must know your mom. There were no honky tonks in our part the country. Beer wasn't even in that county. It's a dry county. There were some shoeshine stands and hamburger stands and something I really came to like-- juke joints and that goes back to what we were talking about, honky tonks. I loved that. I found myself in in church on Sunday morning still thinking about hearing "High Heel Sneakers." The honky tonks got into me real fast with Buck Owens, Lester Frizzell, Ernest Tubb and people like that. They got into my heart real fast.

Moderator: What you're talking about again is class of music, the south. I've been trying to get a handle on it. For one, I started packing around in my head that it's a house. Not a very well-built house, somewhere on the outskirts, it's out in the country, it's not downtown. And it's in your juke joints or honky tonk on a Saturday night and you never know when it becomes a church on Sunday morning. And it's got all these rooms in it and the walls are kinda thin and move back and forth, some of them have blues, some of them have country music, gospel quartet. The doors are always open. Music pouring out. Moderator: What you're talking about again is class of music, the south. I've been trying to get a handle on it. For one, I started packing around in my head that it's a house. Not a very well-built house, somewhere on the outskirts, it's out in the country, it's not downtown. And it's in your juke joints or honky tonk on a Saturday night and you never know when it becomes a church on Sunday morning. And it's got all these rooms in it and the walls are kinda thin and move back and forth, some of them have blues, some of them have country music, gospel quartet. The doors are always open. Music pouring out.

Marty: What you're describing, In my opinion, it's kinda born on a foundation of pain. Case of the blues. Lonesome. It's hard times and misery. There's a lot of pain down there. The foundation of that where some of our finest Southern voices like Hank Williams. He basically started a whole generation of pain or Muddy Waters, same with Robert Johnson.

Moderator: Slavery is the issue. Slavery is another way of force. It cut not only black culture but it cut white culture deeply too. Moderator: Slavery is the issue. Slavery is another way of force. It cut not only black culture but it cut white culture deeply too.

Marty: That's true. Music was probably at some time, the only relief of that magnitude.

Moderator: Enough of the songwriting thing. I'm sure that many in the audience here know that it's a mystery of how you write the song. And how you come up with an album. I must admit, I listened to The Pilgrim and, by the way, if you haven't come in touch yet with The Pilgrim, you need to get it It's a great, great album. And it unlike like to me, so called country album that I've heard in a long time. I think I described it as "richly raw" or some fancy word. It's got 20 songs on it and sometimes they go together and sometimes they come back at you. Go out and get it. Show MCA that art sells. (Heavy applause.) How do you go about putting that together? How do you know what songs to go through?

Marty: I couldn't imagine writing a novel. I write a few verses of prose and that kind of thing, but back to the South, it goes to the stories. It was based on true story that happened in my hometown. Because I've always collected characters. I love characters. I love to sit and talk to people. That's one of my favorite things about that. Everybody has a story. But "The Pilgrim" is a story that basically happened in my hometown. There was a guy that we went to church with named Cross-eyed Norman. And everybody was afraid of him because he had this air about him that he would be snapping at any second. He was really friendly with me and my sister. And his mom had a beauty shop and my mom had her hair done there. I hang out and talk with Norman.

On the other side of town was girl named Freda. The prettiest girl that I'd ever seen. God blessed her with a wildest spirit to ever come out of Mississippi. She was a pure mess. We thought Miss Mississippi, then onto Miss America or something like that. But she had different ideas. And to show her mama and daddy who's boss, the prettiest girl in town married Cross-eyed Norman. And, sure enough, early on in their marriage there was trouble. Norman was very possessive and jealous. And so, she worked down at the hospital and she started flirting with a guy in town that I call The Pilgrim. He fell head over heels in love with her. And they'd have casual conversation. She'd always take her wedding ring off. She never told the guy she was married. And he offered to marry her. And, as you can imagine, things started kept brewing at home. All of a sudden, one day, Norman comes home and for a few days in a row, she hadn't been there to fix supper. And he wrote her a letter and he stopped at his mama's house, he stopped at a friend's house and he drove over to the hospital and found her sitting in the break room having a conversation with this guy. So he went off, he went crazy. He started waving the pistol around. And the guy got up to defend her. And at that time, she finally had to confess and say "that's my husband." He says, "whoa, you forgot to tell me that." He says, "Sir, I had no idea she was married. If you put that gone down, I'll walk out of here and I'll never speak to her again." Norman says, "I came here to show you and her what it does when a man like you messes with my home." By now a crowd had gathered in the room. So, he's waving his pistol around. The Pilgrim stepped in to take him out. And Norman handed her a note and said, "I want to show you how much I love you" and he took his life in front of everyone. I went "whoa." On the other side of town was girl named Freda. The prettiest girl that I'd ever seen. God blessed her with a wildest spirit to ever come out of Mississippi. She was a pure mess. We thought Miss Mississippi, then onto Miss America or something like that. But she had different ideas. And to show her mama and daddy who's boss, the prettiest girl in town married Cross-eyed Norman. And, sure enough, early on in their marriage there was trouble. Norman was very possessive and jealous. And so, she worked down at the hospital and she started flirting with a guy in town that I call The Pilgrim. He fell head over heels in love with her. And they'd have casual conversation. She'd always take her wedding ring off. She never told the guy she was married. And he offered to marry her. And, as you can imagine, things started kept brewing at home. All of a sudden, one day, Norman comes home and for a few days in a row, she hadn't been there to fix supper. And he wrote her a letter and he stopped at his mama's house, he stopped at a friend's house and he drove over to the hospital and found her sitting in the break room having a conversation with this guy. So he went off, he went crazy. He started waving the pistol around. And the guy got up to defend her. And at that time, she finally had to confess and say "that's my husband." He says, "whoa, you forgot to tell me that." He says, "Sir, I had no idea she was married. If you put that gone down, I'll walk out of here and I'll never speak to her again." Norman says, "I came here to show you and her what it does when a man like you messes with my home." By now a crowd had gathered in the room. So, he's waving his pistol around. The Pilgrim stepped in to take him out. And Norman handed her a note and said, "I want to show you how much I love you" and he took his life in front of everyone. I went "whoa."

In the town, it was basically a scandal. After it had died down, this man that was left behind, he was guilty of nothing but loving....all he did was fall in love with another woman that was married. So, he started drinking. And he threw away his status in the community, lost his job, lost his home, went hitchiking and became a ditch drunk. And out there, by his own account, he met a hobo and he became hobo. His only goal in life was to go to California, put flowers on his mama's grave, and drown himself in the Pacific Ocean. When he got out to California, he went out to his mama's grave and then he decided he wanted to hear Freda's voice once more time. So he called back to hear her voice. So right on the phone, she begged him to come back. So the end of the story is he did come back home and a hillbilly singer wrote a record about them. And I told this story, so proud of myself, that it was a pretty good song. Then I said, "no, that's a pretty good record." And it took three years to sit down and write it. In the town, it was basically a scandal. After it had died down, this man that was left behind, he was guilty of nothing but loving....all he did was fall in love with another woman that was married. So, he started drinking. And he threw away his status in the community, lost his job, lost his home, went hitchiking and became a ditch drunk. And out there, by his own account, he met a hobo and he became hobo. His only goal in life was to go to California, put flowers on his mama's grave, and drown himself in the Pacific Ocean. When he got out to California, he went out to his mama's grave and then he decided he wanted to hear Freda's voice once more time. So he called back to hear her voice. So right on the phone, she begged him to come back. So the end of the story is he did come back home and a hillbilly singer wrote a record about them. And I told this story, so proud of myself, that it was a pretty good song. Then I said, "no, that's a pretty good record." And it took three years to sit down and write it.

Moderator: Have you been in touch with them?

Marty: No. They probably want to sue me.

Moderator: But the thing, musically, and I'm not saying....but more than it's unshamed richness in variety, specialized in diversity, musically you listen to an album any more, it's pretty much a consistent style, maybe a slow ballad, maybe a honky tonk. But it ends with Earl Scruggs and Marty playing a bluegrass thing together. How did you come up with that? Why?

Marty: Well first of all, the story line needed a soundtrack. In my opinion, it almost played out like an opera, scene for scene. And I thought, what better state of what you love than give it a country music setting. To play it out. And, it worked. And best thing I love about it, and I thought if I never make another country record, it's what I love and believe in about it. It starts with Ralph Stanley, Emmylou Harris, a vignette by George Jones, Johnny Cash quotes Tennyson, and Earl Scruggs and I play it back. It's just simply a soundtrack. The sounds that I love about the music. The beauty part of it is the versatility. Not only the styles, the indivduality, like I said, but the different places, the different cultures brought to the table when they came to this town to record. And I love that. Marty: Well first of all, the story line needed a soundtrack. In my opinion, it almost played out like an opera, scene for scene. And I thought, what better state of what you love than give it a country music setting. To play it out. And, it worked. And best thing I love about it, and I thought if I never make another country record, it's what I love and believe in about it. It starts with Ralph Stanley, Emmylou Harris, a vignette by George Jones, Johnny Cash quotes Tennyson, and Earl Scruggs and I play it back. It's just simply a soundtrack. The sounds that I love about the music. The beauty part of it is the versatility. Not only the styles, the indivduality, like I said, but the different places, the different cultures brought to the table when they came to this town to record. And I love that.

It was easy to tell where these guys came from. It was easy to tell when Bill Monroe after he set out to play country music, or Bob Wills, or Patsy Cline. Vince Gill's from Oklahoma. He brings a piece of his soul with him. Ricky Skaggs with his mandolin playing.

At this point, the transcription machine ate the tape and I was unable to transcribe the rest of it.

Photos by Mario Mattioli

|

The Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt University in Nashville presented "A Conversation With Marty Stuart" on December 4. Dale Cockrell, Professor of Musicology and American and Southern Studies at the school, was the moderator

The Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt University in Nashville presented "A Conversation With Marty Stuart" on December 4. Dale Cockrell, Professor of Musicology and American and Southern Studies at the school, was the moderator "Yet, there's much more to this man than a litany of top ten hits, a list of his Grammy's (three to date), membership in the Grand Ole Opry. Perhaps no musician in Nashville today is as varied in his position of his talents or more a champion of the music. An excellent singer/songwriter who's among Nashville's very best mandolinist and flat-picking guitarist. He's just back from Los Angeles where he's been working on a movie, his second in two years. And the regard of his peers known for his talent has been indicated in part by his election to the Presidency of the County Music Foundation, an association that promotes the industry and, among other things, oversees the Country Music Hall of Fame.

"Yet, there's much more to this man than a litany of top ten hits, a list of his Grammy's (three to date), membership in the Grand Ole Opry. Perhaps no musician in Nashville today is as varied in his position of his talents or more a champion of the music. An excellent singer/songwriter who's among Nashville's very best mandolinist and flat-picking guitarist. He's just back from Los Angeles where he's been working on a movie, his second in two years. And the regard of his peers known for his talent has been indicated in part by his election to the Presidency of the County Music Foundation, an association that promotes the industry and, among other things, oversees the Country Music Hall of Fame. "All this and Marty Stuart still doesn't know where he fits in. And that doesn't bother him. ‘Actually for most of my life, I've not fit in and that is just fine by me.' Well, I thought I had him pegged and then I opened the pages of Oxford American recently and there's Marty Stuart again as a photographer this time. Marty said it well when he suggested that he specializes in diversity. The term ‘renaissance man' is overused but it seems to apply today. It gives me great pleasure and it brings honor to the Blair School of Music to welcome tonight an extraordinary man and an extraordinary musician, Marty Stuart."

"All this and Marty Stuart still doesn't know where he fits in. And that doesn't bother him. ‘Actually for most of my life, I've not fit in and that is just fine by me.' Well, I thought I had him pegged and then I opened the pages of Oxford American recently and there's Marty Stuart again as a photographer this time. Marty said it well when he suggested that he specializes in diversity. The term ‘renaissance man' is overused but it seems to apply today. It gives me great pleasure and it brings honor to the Blair School of Music to welcome tonight an extraordinary man and an extraordinary musician, Marty Stuart." "One of the things that encouraged me the most, that drew me to Nashville was the individuality that everybody brought to the table. I loved, as a kid to sit and watch it on TV and listen on the radio. Everybody brought their stories. They were allowed to be individualists. It was kinda the badge of honor to do that. I didn't know where I fit or where I belonged but I just knew had to come here. I want to be a part of it. Since that time, I've always surrounded myself with champions. Finding young people that had it in their heart too. And one of the most wonderful things about coming here at such a early age is I had access to wit and wisdom of some of the true masters and architects of American music, the cornerstones of our music. I had their phone numbers (laughs) and I used them. When I wanted to learn more about something that somebody had done, Earl Scruggs or Johnny Cash or Merle Haggard and I the opportunity to call ‘em and I took big advantage of that. But one of the beauties along the way........... see, you wonder ‘why did Lester Flatt hire me?' A 13-year old kid from Mississippi. That's the last thing he needed in his life at that point. And he looked just like Eddie Munster (laughs) and who could kinda play the mandolin. But the lesson that I learned is that he passed it on and I thought, ‘ah, that's what it's about, that's how it's done. God gives it to you; you pass it along.'

"One of the things that encouraged me the most, that drew me to Nashville was the individuality that everybody brought to the table. I loved, as a kid to sit and watch it on TV and listen on the radio. Everybody brought their stories. They were allowed to be individualists. It was kinda the badge of honor to do that. I didn't know where I fit or where I belonged but I just knew had to come here. I want to be a part of it. Since that time, I've always surrounded myself with champions. Finding young people that had it in their heart too. And one of the most wonderful things about coming here at such a early age is I had access to wit and wisdom of some of the true masters and architects of American music, the cornerstones of our music. I had their phone numbers (laughs) and I used them. When I wanted to learn more about something that somebody had done, Earl Scruggs or Johnny Cash or Merle Haggard and I the opportunity to call ‘em and I took big advantage of that. But one of the beauties along the way........... see, you wonder ‘why did Lester Flatt hire me?' A 13-year old kid from Mississippi. That's the last thing he needed in his life at that point. And he looked just like Eddie Munster (laughs) and who could kinda play the mandolin. But the lesson that I learned is that he passed it on and I thought, ‘ah, that's what it's about, that's how it's done. God gives it to you; you pass it along.'  "This past summer, I was at the Uncle Dave Macon Days in Murfreesboro and I ran across some guys playing music just kinda on the side and they were burning it up. And people were crowded around. Film crews around. There were people with microphones. It looked like a Grateful Dead concert. And these guys are lovin' it. I understand they stopped traffic and had to call Nashville finest to break up a traffic jam on Second Avenue a couple of weeks ago. Before we go any further, I wanna show you what I'm talking about. About people who have it in their hearts. One of the most primitive, yet authentic and wonderful form of American music, American country music especially. Please make welcome my friends, The Old Crow Medicine Show."

"This past summer, I was at the Uncle Dave Macon Days in Murfreesboro and I ran across some guys playing music just kinda on the side and they were burning it up. And people were crowded around. Film crews around. There were people with microphones. It looked like a Grateful Dead concert. And these guys are lovin' it. I understand they stopped traffic and had to call Nashville finest to break up a traffic jam on Second Avenue a couple of weeks ago. Before we go any further, I wanna show you what I'm talking about. About people who have it in their hearts. One of the most primitive, yet authentic and wonderful form of American music, American country music especially. Please make welcome my friends, The Old Crow Medicine Show." The six members of the band came out. Mario and I have seen these guys several times and they are quite entertaining. They are all in their early twenties and they don't play a song newer than 1929 or 1930's (so they say). Most play multiple instruments and their sound is a mixture of bluegrass and Appalachian mountain music. They play a lot of Old Time and Bluegrass Festivals. These guys LOVE what they are doing--and it's nice to know that the music is being kept alive by a group of young men. This time, the guys were dressed up a bit. Suits, jackets--some with hats. Marty had to comment "Most of us have been to the Nashville jail before." The audience roared. Marty and the boys traded quips while the instruments were being tuned. Marty then played mandolin with them on two songs. The Old Crow Medicine show left the stage and went to sit down and catch the rest of the evening's event.

The six members of the band came out. Mario and I have seen these guys several times and they are quite entertaining. They are all in their early twenties and they don't play a song newer than 1929 or 1930's (so they say). Most play multiple instruments and their sound is a mixture of bluegrass and Appalachian mountain music. They play a lot of Old Time and Bluegrass Festivals. These guys LOVE what they are doing--and it's nice to know that the music is being kept alive by a group of young men. This time, the guys were dressed up a bit. Suits, jackets--some with hats. Marty had to comment "Most of us have been to the Nashville jail before." The audience roared. Marty and the boys traded quips while the instruments were being tuned. Marty then played mandolin with them on two songs. The Old Crow Medicine show left the stage and went to sit down and catch the rest of the evening's event. Then Marty picked up his acoustic guitar and started playing and it was out of tune. "Whoa" he said. He proceeded to play "Hard Times and Misery."

Then Marty picked up his acoustic guitar and started playing and it was out of tune. "Whoa" he said. He proceeded to play "Hard Times and Misery." Marty: Well, music, pure music, I have no choice. My wife Connie has a saying I really love a lot. She says that "pure music is the cry of the heart." And I love the authenticity of what these guys do. The Old Crow Medicine Show band is just an example. I could have brought people from their age group that play rockabilly music or southern gospel music or blues. But, they're just on file. They're just full of authenticity. I love to baptize them in the same kind of authentic fire. And I love it, I dearly love it.

Marty: Well, music, pure music, I have no choice. My wife Connie has a saying I really love a lot. She says that "pure music is the cry of the heart." And I love the authenticity of what these guys do. The Old Crow Medicine Show band is just an example. I could have brought people from their age group that play rockabilly music or southern gospel music or blues. But, they're just on file. They're just full of authenticity. I love to baptize them in the same kind of authentic fire. And I love it, I dearly love it. Marty: No. There are no Waffle Houses in Los Angeles. We taped an IMAX film on country music this year. Gotta get around to write songs and making records again. After you make a record like The Pilgrim. The difference between The Pilgrim and all the other records I made is The Pilgrim was purely inspired. It wasn't about playing the game. It wasn't about the charts. It's more about the heart. And I knew it would have commercial ramifications. Probably weren't the greatest but spiritually and soulfully, it stands up. As Johnny Cash made the statement to me, he said "once you make a record like that, you can't go back there."

Marty: No. There are no Waffle Houses in Los Angeles. We taped an IMAX film on country music this year. Gotta get around to write songs and making records again. After you make a record like The Pilgrim. The difference between The Pilgrim and all the other records I made is The Pilgrim was purely inspired. It wasn't about playing the game. It wasn't about the charts. It's more about the heart. And I knew it would have commercial ramifications. Probably weren't the greatest but spiritually and soulfully, it stands up. As Johnny Cash made the statement to me, he said "once you make a record like that, you can't go back there." Marty: Yeah! It's a matter of focusing. And I'm from Mississippi so I find myself in the pine trees down there looking for inspiration. Kinda like what Hank Williams said one time, he said, "Hoss, I don't write ‘em. God writes them. I just hang on to the pen."

Marty: Yeah! It's a matter of focusing. And I'm from Mississippi so I find myself in the pine trees down there looking for inspiration. Kinda like what Hank Williams said one time, he said, "Hoss, I don't write ‘em. God writes them. I just hang on to the pen."  Moderator: What did Mississippi give to you as a kid or did it give you anything? What was it like growing up in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Moderator: What did Mississippi give to you as a kid or did it give you anything? What was it like growing up in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Moderator: Did you grow up in church?

Moderator: Did you grow up in church? Moderator: What you're talking about again is class of music, the south. I've been trying to get a handle on it. For one, I started packing around in my head that it's a house. Not a very well-built house, somewhere on the outskirts, it's out in the country, it's not downtown. And it's in your juke joints or honky tonk on a Saturday night and you never know when it becomes a church on Sunday morning. And it's got all these rooms in it and the walls are kinda thin and move back and forth, some of them have blues, some of them have country music, gospel quartet. The doors are always open. Music pouring out.

Moderator: What you're talking about again is class of music, the south. I've been trying to get a handle on it. For one, I started packing around in my head that it's a house. Not a very well-built house, somewhere on the outskirts, it's out in the country, it's not downtown. And it's in your juke joints or honky tonk on a Saturday night and you never know when it becomes a church on Sunday morning. And it's got all these rooms in it and the walls are kinda thin and move back and forth, some of them have blues, some of them have country music, gospel quartet. The doors are always open. Music pouring out.  Moderator: Slavery is the issue. Slavery is another way of force. It cut not only black culture but it cut white culture deeply too.

Moderator: Slavery is the issue. Slavery is another way of force. It cut not only black culture but it cut white culture deeply too.  On the other side of town was girl named Freda. The prettiest girl that I'd ever seen. God blessed her with a wildest spirit to ever come out of Mississippi. She was a pure mess. We thought Miss Mississippi, then onto Miss America or something like that. But she had different ideas. And to show her mama and daddy who's boss, the prettiest girl in town married Cross-eyed Norman. And, sure enough, early on in their marriage there was trouble. Norman was very possessive and jealous. And so, she worked down at the hospital and she started flirting with a guy in town that I call The Pilgrim. He fell head over heels in love with her. And they'd have casual conversation. She'd always take her wedding ring off. She never told the guy she was married. And he offered to marry her. And, as you can imagine, things started kept brewing at home. All of a sudden, one day, Norman comes home and for a few days in a row, she hadn't been there to fix supper. And he wrote her a letter and he stopped at his mama's house, he stopped at a friend's house and he drove over to the hospital and found her sitting in the break room having a conversation with this guy. So he went off, he went crazy. He started waving the pistol around. And the guy got up to defend her. And at that time, she finally had to confess and say "that's my husband." He says, "whoa, you forgot to tell me that." He says, "Sir, I had no idea she was married. If you put that gone down, I'll walk out of here and I'll never speak to her again." Norman says, "I came here to show you and her what it does when a man like you messes with my home." By now a crowd had gathered in the room. So, he's waving his pistol around. The Pilgrim stepped in to take him out. And Norman handed her a note and said, "I want to show you how much I love you" and he took his life in front of everyone. I went "whoa."

On the other side of town was girl named Freda. The prettiest girl that I'd ever seen. God blessed her with a wildest spirit to ever come out of Mississippi. She was a pure mess. We thought Miss Mississippi, then onto Miss America or something like that. But she had different ideas. And to show her mama and daddy who's boss, the prettiest girl in town married Cross-eyed Norman. And, sure enough, early on in their marriage there was trouble. Norman was very possessive and jealous. And so, she worked down at the hospital and she started flirting with a guy in town that I call The Pilgrim. He fell head over heels in love with her. And they'd have casual conversation. She'd always take her wedding ring off. She never told the guy she was married. And he offered to marry her. And, as you can imagine, things started kept brewing at home. All of a sudden, one day, Norman comes home and for a few days in a row, she hadn't been there to fix supper. And he wrote her a letter and he stopped at his mama's house, he stopped at a friend's house and he drove over to the hospital and found her sitting in the break room having a conversation with this guy. So he went off, he went crazy. He started waving the pistol around. And the guy got up to defend her. And at that time, she finally had to confess and say "that's my husband." He says, "whoa, you forgot to tell me that." He says, "Sir, I had no idea she was married. If you put that gone down, I'll walk out of here and I'll never speak to her again." Norman says, "I came here to show you and her what it does when a man like you messes with my home." By now a crowd had gathered in the room. So, he's waving his pistol around. The Pilgrim stepped in to take him out. And Norman handed her a note and said, "I want to show you how much I love you" and he took his life in front of everyone. I went "whoa."

In the town, it was basically a scandal. After it had died down, this man that was left behind, he was guilty of nothing but loving....all he did was fall in love with another woman that was married. So, he started drinking. And he threw away his status in the community, lost his job, lost his home, went hitchiking and became a ditch drunk. And out there, by his own account, he met a hobo and he became hobo. His only goal in life was to go to California, put flowers on his mama's grave, and drown himself in the Pacific Ocean. When he got out to California, he went out to his mama's grave and then he decided he wanted to hear Freda's voice once more time. So he called back to hear her voice. So right on the phone, she begged him to come back. So the end of the story is he did come back home and a hillbilly singer wrote a record about them. And I told this story, so proud of myself, that it was a pretty good song. Then I said, "no, that's a pretty good record." And it took three years to sit down and write it.

In the town, it was basically a scandal. After it had died down, this man that was left behind, he was guilty of nothing but loving....all he did was fall in love with another woman that was married. So, he started drinking. And he threw away his status in the community, lost his job, lost his home, went hitchiking and became a ditch drunk. And out there, by his own account, he met a hobo and he became hobo. His only goal in life was to go to California, put flowers on his mama's grave, and drown himself in the Pacific Ocean. When he got out to California, he went out to his mama's grave and then he decided he wanted to hear Freda's voice once more time. So he called back to hear her voice. So right on the phone, she begged him to come back. So the end of the story is he did come back home and a hillbilly singer wrote a record about them. And I told this story, so proud of myself, that it was a pretty good song. Then I said, "no, that's a pretty good record." And it took three years to sit down and write it. Marty: Well first of all, the story line needed a soundtrack. In my opinion, it almost played out like an opera, scene for scene. And I thought, what better state of what you love than give it a country music setting. To play it out. And, it worked. And best thing I love about it, and I thought if I never make another country record, it's what I love and believe in about it. It starts with Ralph Stanley, Emmylou Harris, a vignette by George Jones, Johnny Cash quotes Tennyson, and Earl Scruggs and I play it back. It's just simply a soundtrack. The sounds that I love about the music. The beauty part of it is the versatility. Not only the styles, the indivduality, like I said, but the different places, the different cultures brought to the table when they came to this town to record. And I love that.

Marty: Well first of all, the story line needed a soundtrack. In my opinion, it almost played out like an opera, scene for scene. And I thought, what better state of what you love than give it a country music setting. To play it out. And, it worked. And best thing I love about it, and I thought if I never make another country record, it's what I love and believe in about it. It starts with Ralph Stanley, Emmylou Harris, a vignette by George Jones, Johnny Cash quotes Tennyson, and Earl Scruggs and I play it back. It's just simply a soundtrack. The sounds that I love about the music. The beauty part of it is the versatility. Not only the styles, the indivduality, like I said, but the different places, the different cultures brought to the table when they came to this town to record. And I love that.